02.01.17 Samaritans. The Samaritans claim to be descendants of Jacob, his son Joseph, and his two sons Ephraim and Manasseh. (cf. Jn. 4:12) but scholarship denies it. In 733 B.C. the Assyrians conquered the ten northern Israelite tribes, known collectively as Israel.[1] In an attempt to destroy the culture and prevent possible future uprisings, about a decade later the Assyrians deported a vast majority of the ten Israelite tribes far to the east. For similar reasons, they imported five foreign tribes from other conquered lands.[2] The Israelites who were not deported intermarried with their new neighbors and their descendants became known as the Samaritans,[3] named after the land of Samaria in which they lived.[4] Amazingly, they followed the Jewish Torah but with several significant changes.

- The Samaritans removed all references pertaining to Jerusalem from their Torah.

- The Samaritans believed that Mount Gerizim instead of Jerusalem was the divine location to offer sacrifice and worship God.

- They believed Mount Gerizim was where God created Adam and Eve.

- The Samaritans also believed Mount Gerizim was where Abraham offered Isaac, and every Samaritan child knew where the thicket bush was where the ram got caught.

- While the Samaritan Torah was modified from the Jewish edition, there is agreement between the two holy books on more than two thousand other passages.[5] Ironically, this reflects accuracy of transmission and translation over many centuries to the modern Bible versions.

- After the Babylonians took the captured Jews of Jerusalem and Judea to Babylon in 585 B.C., the Jews changed their Hebrew alphabet to the Aramaic Square Script. Since the Old Testament until that time was written in the older Hebrew script, the Samaritans felt the Babylonian Jews polluted the Scriptures by making this change. Therefore, the Samaritan form of writing is a much older version of Hebrew, but it too, has undergone some changes throughout history.[6]

- The Samaritans, like so many others in the ancient Middle East, believed that God would send someone soon to restore their land and people. That “someone” was called the Taheb or Restorer – a great prophet of the end-time whom Moses referred to in Deuteronomy 18:15.[7]

- Concerning ritual purity, the Jews were insistent on ritual purity on a variety of issues, but not so the Samaritans. They accepted Greek coins with pagan deities, temples for pagan worship, and even the name Sabaste is the Greek name for Augusta or Augustus.[8] These things the Jews desperately opposed, and they hated the Samaritans for accepting them.

- The Samaritan calendar is different from the Jewish one, making the festival observances at different times than Jewish ones.[9]

02.01.17.A. RUINS OF THE SAMARITAN TEMPLE. The ruins of the Samaritan temple lay beneath the Byzantine ruins in the foreground. The Byzantine church was built to honor the Samaritan temple. Photograph by the author.

Therefore, the Samaritans, like the Sadducees, the Pharisees, the Essenes of Qumran, and all the smaller Jewish sects, they all identified themselves to be “Israelites,” between the years 250 B.C. and A.D. 200.[10] However, the Samaritans did not take on the name “Jew” as did the other sects. If the religious differences were not enough to cause conflicts, actions by both sides intensified the hatred and conflict. The following is an abbreviated list of repulsive actions.

- When the Jews returned from Babylon to Israel to rebuild the temple, a Horonite (Samaritan) by the name of Sanballat harassed them with the help of a “garrison in Samaria” (Neh. 4:2).[11]

- When the Greek General Alexander the Great conquered this part of the world, he destroyed the Samaritan cities but left Jerusalem untouched.[12] This caused jealousy.

- But a little more than a century later during the Maccabean Revolt, when the Jews fought against the Syrian Greeks, they had to fight the Samaritans as well.

- During the Revolt, the Samaritans to advantage of every opportunity to capture Jews and sell them into slavery.

- In 128 B.C. when John Hyrcanus became the Jewish governor and high priest, he destroyed the Samaritan temple.[13]

- In 107 B.C., Hyrcanus destroyed the Samaritan city of Shechem.[14]

- In 63 B.C. when the Romans conquered the Jewish lands and the Samaritans again fought against the Jews.[15]

- Between the years 40 to 37 B.C., when Herod the Great fought various political and criminal entities to gain control of the Jewish nation, the Samaritans fought with him.

- Josephus recorded a number of accounts where the Samaritans attacked the Jews. In one such case, when the temple gates were opened at midnight to accommodate the worshipers with their Passover lambs, a number of Samaritans entered and desecrated the temple by throwing human bones throughout the sanctuary.[16] This sacrilege occurred shortly after Coponius, the first procurator after Archelaus, was deposed.

- At this time it was common practice that priests would give trumpet and fire signals from the pinnacle of the temple to mark the beginning of the Sabbath, the beginning of a month, and special festivals. The fire signals were repeated from one hill-top community to another, and within minutes all Israel knew when that the Sabbath had begun.[17] The Samaritans would at times set off a false signal, much to the anger of the Jews who had been deceived.

- At times, when Jews traveled from Galilee through Samaria on their way to Jerusalem, they were beaten and sometimes killed. However, leaving the Holy City and returning north to Galilee was always seen as a good thing by the Samaritans.

Little wonder then that by the time Jesus came on the scene the social tension was extremely volatile. This is seen in John 8:48, when the accusers referred to Jesus as a Samaritan. It was in the cultural context and connection that, in rabbinic demonology, a leading demon was named Shomroni, which was also used to refer to either a demon or Samaritan.[18] Obviously this reflects the tension between the two groups. Yet according to John 4 and the book of Acts, missionary efforts in Samaria were successful in the early years of the church.[19]

In light of these hostilities, the words and work of Jesus were absolutely profound. Imagine what the Jews thought when Jesus told the parable of the Good Samaritan, or when He healed the ten lepers, and only the Samaritan returned to thank Him. Jesus was not only a profound Person to the Jews, but also to the Romans who were quietly watching Him with the help of the Herodians.

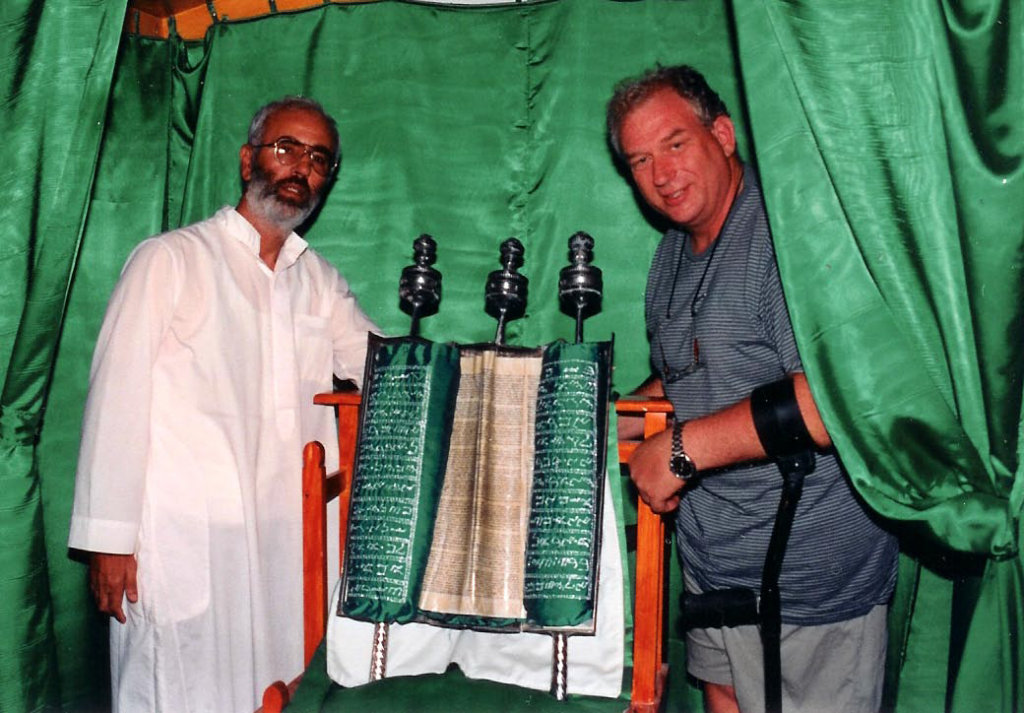

02.01.17.B THE SAMARITAN TORAH SCROLL. Husney W. Kohen, Director of the Gerizim Center and Museum as well as the future Samaritan high priest, discussed the Samaritan Torah Scroll and faith with the author in 1999. Photo by translator Arie bar David.

[1]. New International Version Archaeological Study Bible. (notes) 1737. See 03.02.04 “733 B.C. Israel Falls To The Assyrians; Israelites Deported To The East; 723 B.C. Israel Ends”

[2]. Gaster, “Samaritans.” 4:190-93.

[3]. As of this writing, the total population of the Samaritans is under one thousand. They still practice their religious rituals such as Passover sacrificial offerings, as during the time of Christ. They claim to be descendants of the tribes of Levi, Ephraim, and Manasseh. They further claim to have maintained a continuous priesthood from Aaron (brother of Moses) through Eleazar and Phinehas until the 17th century A.D.

[4]. Cf. 2 Kg. 17; see also 03.02.04; Anderson, R. T. “Samaritans.” 303; La Sor, “Samaria.” 4:298-303.

[5]. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 19 n. 27.

[6]. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 18-20.

[7]. Bruce, New Testament History. 34-35; Scott, Jr. Jewish Backgrounds of the New Testament. 200. See also 06.01.03.

[8]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:51, 117.

[9]. Scott, Jr. Jewish Backgrounds of the New Testament. 200.

[10]. Charlesworth and Evans, The Pseudepigrapha and Early Biblical Interpretation. 22.

[11]. Sanballat is among fifty biblical names whose existence has been verified by archaeological studies in a published article by Lawrence Mykytiuk titled, “Archaeology Confirms 50 Real People in the Bible.” Biblical Archaeology Review. March/April, 2014 (40:2), pages 42-50, 68. This archaeological evidence confirms the historical accuracy of the biblical timeline. For further study see the website for Associates for Biblical Research, as well as Grisanti, “Recent Archaeological Discoveries that Lend Credence to the Historicity of the Scriptures.” 475-98. However, some scholars debate the identity of Sanbalat as there was more than one individual of importance by this name. For example, there is a Sanbalet mentioned in the Elephantine Papyri; a literary work written by Jews who escaped the Babylonians and Persians in the 6th century to live on the island of Elephantine in southern Egypt. The name also appears in the Wadi Daliyeh papyri (4th cent. B.C.).

[12]. Kelso, “Samaria, City of.” 5:238.

[13]. Some scholars believe Hyrcanus destroyed the Samaritan temple in 108 B.C.

[14]. Kelso, “Samaria, Territory of.” 5:242; Lang, Know the Words of Jesus. 283.

[15]. Gaster, “Samaritans.” 4:191-96.

[16]. A.D. 6 or 7; Josephus, Antiquities 18.2.2; Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:293.

[17]. Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament. 2:113.

[18]. Fruchtenbaum, The Jewish Foundation of the Life of Messiah: Instructor’s Manual. Class 16, page 2.

[19]. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 19-21.