02.03.08 Language. For more than a century many scholars were convinced that first century Jews in Judaea did not speak Hebrew, but Greek, and to a lesser degree, Aramaic. The irony is that Aramaic is a sister language to Hebrew.[1] Some even believed that Hebrew was a lost language in the first century stating that it was lost during the exile. However, would a people lose their language in 50 or 70 years? They did not lose it in Egypt in four centuries.

Today scholars understand that Aramaic was generally the language of the common people, Hebrew was the sacred language of religious worship and of scribal discussion, and Greek was the linguistic medium for trade, commerce, and government administration.[2] The biblical books written during and after the exile were mostly written in Hebrew.[3] The Mishnah was written in Hebrew and the bar Kokhba letters were written in Hebrew. The gospels were written in Hebrew or possibly Aramaic, but not Greek.

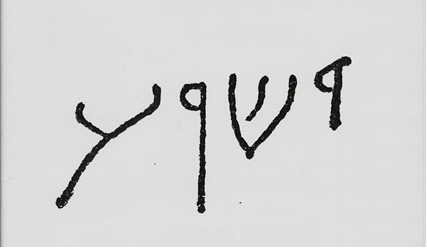

02.03.08.A THE NAME “JESUS” IN OLD SEMETIC SCRIPT. The name of Jesus, or Yeshua, as He may have written it in the Old Semitic Script, although the new Aramaic Square Script had gained popularity. This example was taken from an ossuary (bone box) of someone else by the same name, Yeshua.

This erroneous belief has affected a few translations of the Bible. For example, in the New International Version of the Bible (1984), the phrase “in Aramaic” really should read, “in Hebrew” in Acts 21:40, 22:2, and 26:14. To complicate matters the standard New Testament Greek lexicon also endorses the same error.[4] Yet Aramaic was the language spoken by Jesus in daily life and His Aramaic words are recorded in Mark 5:41 and 15:34. The leading Pharisees spoke only Hebrew as not to be associated with the common people.[5] Today Aramaic remains the language taught and spoken in religious schools in Armenia.[6] Since Aramaic and Hebrew are sister languages, the differences are small. For example, the English name of Jesus, son of Joseph in Aramaic is Yeshua bar Yosef while in Hebrew it is Yeshua ben Yosef. Both mean Yeshua, son of Joseph, or Jesus, son of Joseph. In both languages, the letter “J” becomes a “Y.”[7]

While all languages change slowly over the centuries, some change rapidly as the culture changes. In the lands of the ancient Assyrians and Babylonians, there had been few changes until the twentieth century. After studying the languages in the region, some Bible translators have concluded that a dialect known today as “Aramaic M-South” is the closest form of Aramaic commonly spoken in the days of Jesus.[8]

In Babylon, the Jews spoke Aramaic. It had been the lingua franca, or language of commerce, throughout the Persian Empire since the sixth century (B.C.) and when they returned home to Judaea, they naturally spoke it along with Hebrew. But with the advancement of the Greek culture, orthodox Jews in Israel rejected the Greek language because they did not want their children to be absorbed into Hellenism. This was in stark contrast to those living in Alexandria, Egypt, where Greek became so common that the Scriptures were translated into Greek[9] so the youth could read it.

When Antiochus IV Epiphanes came to power in the third century B.C., Greek became the language of all legal and political matters, although Aramaic remained in common use. Classical Greek had died out and was replaced with koine Greek – the language of the common people. This remained unchanged in the days of Jesus, although Latin was gaining a foothold. By the first century, the Greek language belted the Mediterranean Sea, which permitted the gospel to be preached effectively to many people groups, nearly all of whom spoke the same language. A study published in 1992 revealed that 40 percent of pre-A.D. 70 burial inscriptions are in Greek.[10] Clearly the language was well established. The fact that the Greek language became accepted over a massive area, was beneficial not only for the spread of the gospel, but also for the Romans. Their empire was so massive that it had hundreds of people groups with many languages and dialects. Alexander the Great reduced those languages to twelve.

When the Maccabean Revolt brought victory in the early second century B.C., there was a revival of Hebrew as evidenced on coins, ostraca,[11] and papyrus fragments, all of which have Hebrew writing. The Dead Sea Scrolls, various inscriptions, and other fragments written by the orthodox Jews are seldom found to be in Aramaic, Greek, or Latin, but were written in Hebrew. At Masada, Hebrew writings were found on fourteen scrolls, 4,000 coins, and 700 ostraca.[12] Archaeological discoveries show that Hebrew writings were more common than Aramaic by a ratio of nine to one.[13]

The land of the Jews was literally a little enclave of a subculture surrounded by Hellenistic peoples. Even within its borders, Samaria and the Decapolis city of Beit Shean (also known as Scythopolis), were two Hellenistic strongholds. Consequently, the Jewish cultural island was constantly inundated with Greek philosophies, religion, and temptations. There is no question then that the Jewish people were very familiar with the Greek ways of life and thinking.[14] It is generally accepted that Jesus read from a Hebrew scroll, spoke to the crowds in Aramaic, and conversed with the Roman authorities in Aramaic or Greek. While Latin was the official language of Rome, it was seldom used in Israel. The Empire was so enormous that it had 12 language groups.

The introduction and use of koine Greek was an important development in preparing the world for the gospel.[15] Of all the ancient languages, this was the best medium for the accurate expression of ideas. The vocabulary is clearly extensive in philosophical, ethical, and religious concepts. Hebrew is a pictorial language using phrases such as “He is my rock,” or “cleft of a rock,” whereas Greek is more descriptive of human emotions and virtues. Jesus used verbal pictures of objects, plants, animals, and most of all, people, in teachable moments to convey His message of the Kingdom of God.[16] Furthermore, and so importantly, He repeatedly connected these to various Old Testament passages.[17]

Video Insert >

02.03.08.V1 Unique Challenges of the Greek and Hebrew Languages. Dr. John Soden presents unique insights into the Greek and Hebrew languages.

Were it not for the advent of Hellenism, the New Testament would not have been written in the Greek which brought a new realm of words to express emotions and thought.[18] Hebrew is not a language that is rich with adjectives.[19] Therefore, a phrase might read, “a son of quarrels,” rather than “a quarrelsome man.” Another example is to say that he was a “son of God” rather than saying he was a “godly man.” The expressions of “Son of Man” and “Son of God,” express the deity of Jesus,[20] but the former title also asserts His humanity.[21] The beauty of the Greek language is that it introduced adjectives that enriched the meaning and understanding of the New Covenant. Yet it was Jesus Himself who introduced at least one change – He introduced the term Abba[22] (means Daddy, 5)[23] in the Lord’s Prayer, as this revealed that prayers were welcomed in any language.[24] He revealed to the Jewish people that Hebrew was no longer the exclusive “language of God.”[25]

Video Insert >

02.03.08.V2 An Introduction to Greek and Hebrew Words. Dr. Joe Wehrer discusses some unique characteristics of Greek and Hebrew Words.

It is clear that whatever New Testament books were written in Hebrew – namely Matthew and possibly Hebrews – these were almost immediately translated into Greek. While some early Church fathers have stated that two books were written in Hebrew, nearly all papyrus fragments and scrolls discovered are in Greek. The New Testament was primarily written in Greek for the benefit of the Gentiles and Jews living in foreign countries. The strong isolationists, who desired to keep the Hebrew language and culture separate, did not prevent the gospel from quickly spreading throughout the Roman Empire. However, because of the Second Revolt (A.D. 132-35), the Hebrew language had nearly disappeared, with the exception of use in the synagogues and yeshivas (seminaries). It would lie dormant for nearly seventeen centuries before being revived in a modified form in modern Israel.

[1]. Mishnah, Megillah 4:4,6,10; Mishnah, Sotah 7:2.

[2]. Witherington III, Ben. “Almost Thou Persuadest Me…” 67.

[3]. Daniel, Chronicles, Nehemiah, Ezra, Malachi, Haggai, Zechariah, Ezekiel.

[4]. Bauer, Arndt, and Gengrich, A Greek Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature. 213.

[5]. Bailey, Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes. 292.

[6]. An excellent resource for further biblical study is Ethelbert W. Bullinger’s book titled Figures of Speech Used in the Bible. (Grand Rapids: Baker. 1898, 1995). For more than a century it has been the classic resource tool for the serious Bible student.

[7]. http://boards.straightdope.com/sdmb/showthread.php?t=231844 Retrieved January 14, 2015.

[8]. Moore, “New Life for Ancient Aramaic.” 15. This publication is produced by The Seed Company, a Bible Translation ministry located in Santa Ana, California. For more information, see www.theseedcompany.org.

[9]. See “Septuagint” in 02.02.25.

[10]. Cited by Scott, Jr. Jewish Backgrounds of the New Testament. 117 n9.

[11]. An ostraca is a pottery fragment that was used as a writing surface or material, since papyri and parchment were extremely expensive. See “ostraca” in Appendix 26 for more details. An example is the King David Fragment at 03.02.01.A

[12]. See Appendix 26.

[13]. Bivin and Blizzard, Understanding the Difficult Words. 37.

[14]. Schurer, The History of the Jewish People. 2:75-79.

[15]. See also 03.05.12 “Summary Influence of ‘Hellenistic Reform’ (331 – 63 B.C.) that shaped Jewish life in the First Century.”

[16]. Mould, Essentials of Bible History. 306-08.

[17]. Horne, Jesus the Teacher. 77, 83, 93.

[18]. Mantey, “New Testamentt Backgrounds.” 3:3-14.

[19]. Mould, Essentials of Bible History. 306-08.

[20]. Jn. 3:13; 5:27; 6:27; cf. Mt.26:63-64; Tenney, The Gospel of John. 105.

[21]. Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament. 1:312.

[22]. While the term abba has often been defined as a child’s expression of daddy, language scholar James Barr has suggested that abba was a solemn adult address to father. See Pilch, The Cultural Dictionary of the Bible. 2.

[23]. Vine, “Abba.”Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary. 2:1.

[24]. Jeremias, The Prayers of Jesus. 14-16.

[25]. Bailey, Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes. 95. The term Abba appears in Mk. 14:36; Rom. 8:15; Gal. 4:6.