12.01.05 Lk. 10:25-37

PARABLE OF THE GOOD SAMARITAN

25 Just then an expert in the law stood up to test Him, saying, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?”

26 “What is written in the law?” He asked him. “How do you read it?”

27 He answered: Love the Lord your God with all your heart, with all your soul, with all your strength, and with all your mind (Deut. 6:5); and your neighbor as yourself (Lev. 19:18).

28 “You’ve answered correctly,” He told him. “Do this and you will live.”

29 But wanting to justify himself, he asked Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”

30 Jesus took up the question and said:

A “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho and fell into the hands of robbers.

They stripped him, beat him up,

and fled, leaving him half dead.

B 31 A priest happened to be going down that road.

When he saw him,

he passed by on the other side.

C 32 In the same way, a Levite, when he arrived at the place

and saw him,

passed by on the other side.

D 33 But a Samaritan on his journey came up to him, and

when he saw the man,

he had compassion.

C’ 34 He went over to him

and bandaged his wounds,

pouring on oil and wine.

B’ Then he put the him on his own animal,

brought him to an inn

and took care of him.

A’ 35 The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper, and said. ‘Take care of him. When I come back I’ll reimburse you for whatever extra you spend.’

36 “Which of these three do you think proved to be a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?”

37 “The one who showed mercy to him,” he said. Then Jesus told him, “Go and do the same.”

Literary Style.[1] The poem is written in the style of step parallelism in which each stanza has three lines. From stanzas A to C’, the first line is one that describes an action by someone. This action is a “come” action. The middle line of every stanza of the parable is a “do” action. The last lines of the first five stanzas are a “go” action of some sort. The Samaritan who demonstrated compassion did care for the injured traveler, as expressed by the last line of stanzas C’ to A’ which are also “do” actions in that he took care of the injured.

Cast of Characters

The Traveler = The injured victim of robbery who was lying on the side of the road.

The Priest = A servant of man and God, who lived and functioned with numerous restrictions and responsibilities.

The Levite = An assistant to the priest in the temple who had fewer life restrictions and responsibilities.

The Samaritan = A member of an ethnic group hated by the Jewish people, but who truly demonstrated the love of God.

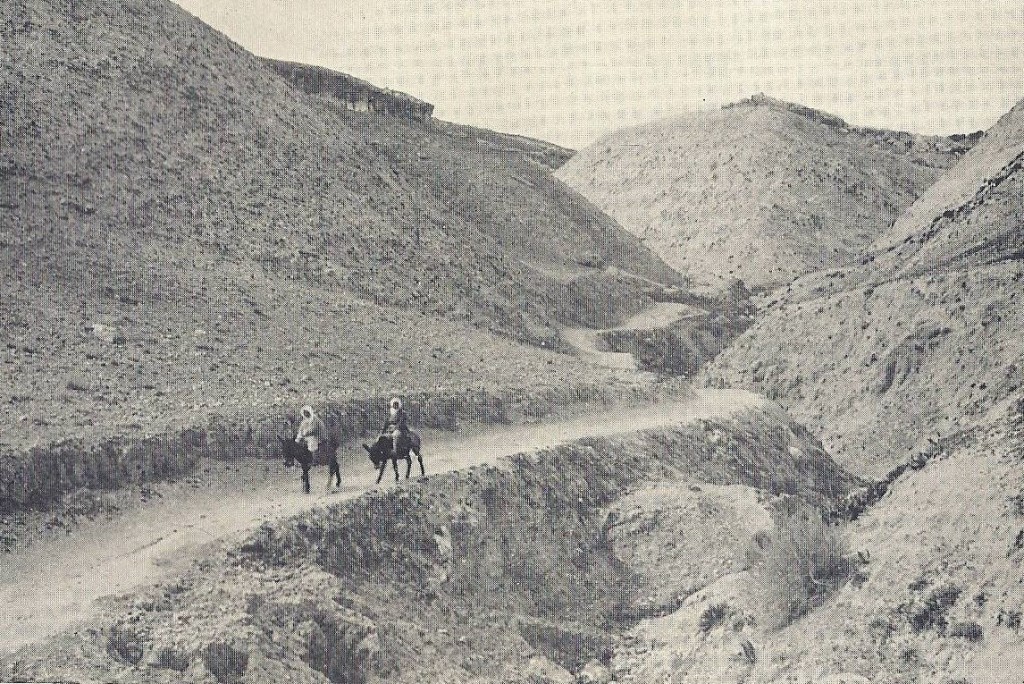

The story takes on realism because many priests and Levites lived in Jericho where a large synagogue was constructed by the Hasmoneans in the previous century. In fact, it has been estimated that about half the courses that served in Jerusalem (see 04.03.01) lived in Jericho,[2] meaning they would have traveled the road of the Good Samaritan parable. The Jericho to Jerusalem road is a winding, narrow road that was at times cut into the side of a mountain with an upward cliff on the south side and a sheer precipice on the north side with a drop of hundreds of feet down into a wadi below. Along this road, Zealots robbed traveling pilgrims and Romans who had limited opportunities to escape.

Jesus put the setting of the parable along a five mile section of the 16 mile road that for centuries had a reputation as being extremely dangerous[3] – known as “the Bloody Way.”[4] For reasons of safety, men frequently carried short concealed swords and families traveled in groups or camel caravans, such as Mary and Joseph did on their journey to and from Egypt, and later when they and Jesus (aged twelve) went to the temple.[5] Those who traveled to and from Jerusalem for religious observances traveled in festival caravans.[6] At the time when Herod the Great was given rulership of the land, the whole region was filled with highway robberies, some of which continued throughout Roman occupation.[7]

Traveling for the Galileans was always a challenge. If they went through Samaria they were in danger of attack by the Samaritans; if they went via Jericho they were in danger of robbers. Josephus said that the Samaritans killed a “great many” Galileans who were in route to Jerusalem, which clearly reflected the danger.[8] Galileans, therefore, frequently traveled south by taking a road located on the eastern side of the Jordan River in Perea. When they arrived near Jericho, they turned westward, crossed the river, went to the rebuilt city of Jericho and rested.[9] From there they walked up the Jericho-Jerusalem Road through the narrow Wadi Kelt canyon walls and on to the Holy City.

To insure maximum safety, people traveled in groups with the following formation:

- Several men would lead the procession.

- Then came the women, children, and possibly a few animals

- Several men were at the end of the group who served as a rear guard.

Country roads were always dangerous, which is why the Essenes never carried anything but a small sword. One would ever walk alone on this country road unless it was absolutely necessary. In fact, Josephus recorded that Judea was full of robberies;[10] therefore, this parable of Jesus had a dynamic reality to the listeners. While the road was open for tourists during the 1990s, as of this writing it is closed due to Palestinian bandits and terrorists.

12.01.05.A. THE DANGEROUS CLIFFS OF THE WADI KELT ALONG THE JERICHO-JERUSALEM ROAD. Shown is a side road to the 16 mile road, known as the Way of Blood,[11] is the setting for the Parable of the Good Samaritan, was a treacherous road cut into steep hillsides and mountains. People traveled in groups for protection from would-be robbers even though Roman soldiers patrolled the area to insure safety. Photograph by the author.

In this parable, an expert in the law – presumably a scribe – stood up to challenge Jesus. Even though his intention was a verbal confrontation, it was with respect. Teachers sat when teaching and students stood in respect to their teacher, especially when speaking. In true Jewish style, the gentleman stood to address Rabbi Jesus about the requirements needed to inherit eternal life. The answer is not a check list of things to do, such as the Ten Commandments, or a philosophical concept, as might be expected by the lawyer (“Scribe”) or by modern Westerners.

In response, Jesus who was seated tells a story of a traveler who was robbed, beaten, and left for dead along the only road from Jericho to Jerusalem. Technically, the physician Luke said he was half dead (Gk. hemithanes 2253), and obviously in grave condition. Jesus then identifies three men who walked by and what they did. The Samaritans were highly despised for reasons previously discussed. The priest and Levite were men of a high religious order; men who were to reflect the character and compassion of God, but chose not to offer assistance. The priests were descendants of Aaron, while the Levites were descendants of Levi. Each group had a different, but important function in the temple. The Priests could take part in the sacrifices and enter the inner sanctuary, while the Levites insured protection of the temple grounds and sang in the choirs.[12] Both the Levite and priest were concerned about becoming defiled if they touched a man who was dead. They did not even care enough to see if he was still alive and possibly help him, only that they might become defiled. The Samaritan, on the other hand, had the same restrictions according to the Samaritan Torah, but he was not only willing to take the chance and become defiled, but then he helped the wounded man and paid for his medical attention.

The lifestyles of the priests were highly restricted by the Mosaic Law. For example, if a priest touched a corpse he would be defiled, but the law did not apply to Levites (even though they were concerned about defilement). This was one of 613 commands in the Law of Moses (248 positive, 365 negative).[13] However, the Law also stated that priests and Levites were required to offer assistance to save a life. But in the story, they chose not to. Then the Samaritan came who offered assistance to the stranger. He obviously was the good neighbor who demonstrated obedience to the Mosaic Law where the priests and Levites failed.[14]

12.01.05.B. THE UPPER SECTION OF THE JERICHO-JERUSALEM ROAD. The famous road is shown as it was in the 1920s. Throughout history it was a passageway notorious for high risk travelers who traveled alone or in small groups. Photograph by Mary Morton / Public Domain.

“Strength.” The Greek word is Dunamis (1411), and is often ascribed to the power of God (Rev. 5:12, 7:12). Clearly the love to be expressed by believers is to the full human potential, and then more.[15]

“Neighbor.” The Greek term plesion (4139) refers to a specific person, whereas the plural form (geiton, 1069) in the New Testament refers to anyone living in the same land.[16] Jesus obviously rejected the popular opinion that a neighbor was only a fellow Jew. In the first century, people maintained strong ethnic ties and were identifiable by the style of clothing they wore. Clothes were a type of identity badge that displayed the economic status, tribal affiliation, social, and religious affiliation of a person. Back then as now, clothes, language, or accent were markers that distinguished “them from us.” [17] Over the years the religious leaders had redefined the word “neighbor” in the Mosaic command (Lev. 19:18) to mean those who wore the same clothes. The parable specifically stated the man who was robbed and injured was also without his clothes, meaning, he had no social identification and, evidently, could not communicate (Lk. 10:30).[18] So he was no one’s neighbor.

12.01.05.C. THE RUINS OF A TURKISH MILITARY OUTPOST ALONG THE JERICHO-JERUSALEM ROAD. This abandoned outpost, dated to the Ottoman Empire (1517-1917), was reflective of the centuries-old problem travelers had with robbers along the feared Jerusalem-Jericho Road. Soldiers stationed here protected travelers from robbers. It was constructed in front of a natural cave so the soldiers would be protected from the desert heat. Photograph by the author.

The Parable of the Good Samaritan (nowhere in the Bible is he called “good”) was given by Jesus to answer the question posed by an expert of the law: “And who is my neighbor?” The answer by Jesus was “Anyone who has a need.” To illustrate the question, “who is my neighbor?” Jesus used the parable because His listeners were aware of the traveling dangers associated with the road and, as such, it was the subject of other stories.

The Levite and priest were probably concerned about their own purity should the injured man die while in their care. They preferred the man to suffer death rather than take the chance of becoming “unclean.” The irony is that the Levites not only served in the temple, but they also acted as clergy throughout the land and were responsible for social welfare. If anyone should have taken care of the poor traveler, it should have been the Levite.

From the Mishnah is the following narrative that was probably their concern:

A high priest or a Nazarite may not contact uncleanness because of their (dead) kindred, but they may contract uncleanness because of a neglected corpse. If they were on a journey and found a neglected corpse, Rabbi Eliezer says: “The high priest may contract uncleanness but the Nazarite may not contract uncleanness.” But the sages say: “The Nazarite may contract uncleanness but the high priest may not contact uncleanness.” Rabbi Eliezer said to them: “Rather let the priest contract uncleanness for he needs not to bring an offering because of his uncleanness, and let not the Nazarite contract uncleanness for he must bring an offering because of his uncleanness.” They answered: “Rather let the Nazarite contract uncleanness, for his sanctity is not a lifelong sanctity, and let not the priest contract uncleanness, for his sanctity is a lifelong sanctity.”

Mishnah, Nazir 7.1

In a unique manner, Jesus answered the question, “And who is my neighbor?” from the point of cleanliness, since that was a major issue in first century Judaism. The parable intensified the popular rabbinic story and Jesus used it to demonstrate that to show love, compassion, and mercy to someone in need was far more important than the traditional “cleanliness.”

12.01.05.D. THE GOOD SAMARITAN INN. Legend said there once was an inn midway between Jericho and Jerusalem. That legend was based on a khan, or way station, that was built by the Sultan Ibrahim Pasha (1494-1536) of the Ottoman Empire for traveling camel caravans. Since such facilities were generally built upon the ruins of previous ones, the khan added credibility to the legend. However, the legend was not taken seriously until in the late 1990s when evidence was found of a Byzantine church that commemorated an ancient inn. Visitors today can see the evidence of the Byzantine church that commemorated the inn that once stood at this site, and was probably referred to by Jesus. Photographed by the author in 2003 when the archaeological site was under restoration.

The religious elite had two serious obligations or yokes under which they lived.

- The Vow of Neeman that pertained to tithing[19] and

- The Vow of Chabber that pertained to living ritually pure lives.[20]

It is the second vow that was taken to an extreme and is demonstrated here. The exaggerated attitude of purity held by the priest can be seen in the Apocryphal book of Ben Sirach 1:1-7. Here lies the sentiment that undoubtedly saddened Jesus. The priests were instructed not to help those who were sinners, because supposedly, God hates sinners. The narrative is as follows:

If you do a kindness, know to whom you do it,

and you will be thanked for your good deeds.

Do good to a godly man, and you will be repaid –

if not by him, certainly by the Most High.

No good will come to the man who persists in evil

or to him who does not give alms.

Give to the godly man,

but do not help the sinner

Do good to the humble,

but do not give to the ungodly;

hold back his bread,

and do not give it to him

(lest by means of it he subdue you);

for you will receive twice as much evil

for all the good you do to him.

For the Most High also hates sinners

and will inflict punishment on the ungodly.

Give to the good man

but do not help the sinner

Ben Sirach 12:1-7[21]

“Pouring on oil and wine.” Olive oil had numerous uses in the ancient world. In this parable, it was used as a medical remedy for injuries. It was also used in religious services in the temple and for lamps in the home (Mt. 25:1-13). It was used as a condiment (Judges 9:9; Hosea 2:8), for baking (Num. 11:8), and even used after a bath (Ruth 3:3; 2 Sam. 12:20). In an anointing context, it was used to anoint the king upon his coronation (1 Sam. 10:1; 16:1, 13), priests (Lev. 8:30), prophets (Isa. 61:1), and for certain sacrifices (Lev.2:4). In the New Testament it was used by the elders of the church to anoint the sick. Wine has antiseptic qualities and they understood that it had beneficial effects on open wounds.

It should be noticed that the Good Samaritan performed his good deed without any pious phrases or self-congratulation on his own virtuous action. In Luke 10 there is no response given by the lawyer, because the reader is to place himself in that position and answer the question. Yet what the Good Samaritan did will not qualify for eternal life. In the Parable of the Sheep and Goats (Mt. 25:31-46) there are two groups of people standing before God on the day of the last judgment. One group repeatedly demonstrated mercy and kindness to those in need and the other group didn’t. What Jesus said is that true faith takes action in helping others.

Finally, it is unfortunate that for some seventeen or eighteen centuries this parable and many others were not been properly understood. The well-known and highly respected early church father, St. Augustine, was convinced this parable was an allegory with hidden meanings. Three examples of his allegorical interpretations are as follows:

- A “certain man” who was going down to Jericho was the first Adam.

- “Jerusalem” was thought of as the heavenly city, where God lives and from which the first Adam was thrown out.

- “Jericho,” was affiliated with man’s mortality.

Each character in the parable was given a name and function that had some type of spiritual application. But his interpretations are clearly not what Jesus had in mind.[22]

A Lesson in First Century Hermeneutics:

12.01.05.X Use Of Known Stories And Events

As Christian believers who are removed from the historical event by two thousand years, it is difficult to comprehend the cultural setting of various gospel narratives. Hence, the belief that since the words of Jesus are divinely inspired, every story and parable is an original idea with Him. In reality, Jesus used stories and concepts with which the people were already familiar. He spoke of fishing, bread, losing a coin, and many other events that His listeners had already experienced.

These are stories to which His listeners could relate. What is difficult, however, is for the modern student to comprehend what stories, fables and legends were common in the first century. His words were obviously inspired and original and were presented in a manner that His listeners, who had no books, television, radio, or recording devices, could remember. He not only used parables and poetic genre as a memory tool but also existing stories of history, common sayings, current events, and He adapted all of them to His message. Therefore, His parables were not quickly forgotten.

< ——————————————– >

[1]. Bailey, Poet and Peasant. Part I, 72 and Part II, 40; Fleming, The Parables of Jesus. 62.

[2]. Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica. 3:9.

[3]. Josephus, Antiquities 20.6.1 (118); Wars 2.15.6 (232).

[4]. Gilbrant, “Luke.” 335; Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 336.

[5]. Josephus says that the Essenes, when traveling, carried nothing but swords because they feared the thieves. Wars 2.8.4; Wars 2.15.6 (232); Antiquities 20.6.1(118).

[6]. Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 59; Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 2:278; Farrar, The Life of Christ. 364.

[7]. Mishnah, Berakhoth 1.3; Mishnah, Shabbath 2.5

[8]. Josephus, Antiquities 20.6.1. The Samaritans, however, did not threaten the Jews when they left Jerusalem and traveled towards Galilee. It was a symbolic gesture stating that leaving Jerusalem, symbolic of Judaism, was good.

[9]. The ancient city of Jericho was destroyed, never to be rebuilt. A new city by the same name was built a short distance from the ancient ruins of the first.

[10]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.11.8.

[11]. Gilbrant, “Luke.” 335; Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 336.

[12]. Guignebert, The Jewish World in the Time of Jesus. 59-60.

[13]. Carter, 13 Crucial Questions. 57.

[14]. The Samaritans believed in a slightly modified version of the Mosaic Law. See 02.01.17 for the basics of their theological beliefs.

[15]. Vine, “Ability, Able.”Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary. 2:2.

[16]. Vine, “Neighbor.”Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary. 2:429-30.

[17]. Bailey, Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes. 292.

[18]. Bowman, Jesus’ Teaching in its Environment. 31-32; Bailey, Jesus through Middle Eastern Eyes. 292-93.

[19]. Lee, The Galilean Jewishness of Jesus, 112.

[20]. Edersheim, The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah. 216; Lee, The Galilean Jewishness of Jesus, 112.

[21]. Metzger, The Apocrypha of the Old Testament. 143.

[22]. Mowry, “Allegory.” 1:82-84.