08.02.03 Mt. 5:31-32 (See also Mt. 19:9; Mk. 10:12)

DIVORCE ISSUES DEBATED

31 “It was also said, Whoever divorces his wife must give her a written notice of divorce (Deut. 24:1). 32 But I tell you, everyone who divorces his wife, except in a case of sexual immorality, causes her to commit adultery. And whoever marries a divorced woman commits adultery.

The entire issue of divorce and remarriage was a hotly debated issue in the first century. Some desired a strict adherence to the Mosaic Law (Deut. 24:1-5), while others believed that such strictness, at times was too harsh. Into this religious environment entered the influences of Hellenistic culture resulting in a bottomless quagmire. The debates often centered on the meaning of the word “indecent” used by Moses (Deut. 24:1-5), as its definition, was thought to have changed in the fourteen centuries that had transpired since it was written.

The School of Hillel said that a man could consider a divorce “for any disgust, which he felt toward her.” This essentially was the first century equivalent of no-fault divorce. Opposing this view was the School of Shammai, which stated that divorce could take place only in cases of obvious unfaithfulness. Stoning was not discussed. To make matters worse, according to Jewish writings (Sif. Num. 99) Moses, himself, was divorced. He had married Zipporah (Ex. 2:21), but “sent her away,” (meaning a divorce) to her father (Ex. 18:2) and then married a Cushite (black African from Ethiopia) woman (Num. 12:1). This second marriage quickly became the subject of bitter discussions between Miriam[1] and Aaron (Num. 12:1).[2] Those discussions concerning divorce continued to the time of Jesus.

Clearly, Jesus forbids divorce, not on the Mosaic regulations of divorce, but on the purpose of God instituting marriage. In doing so He eliminated all the arguments between the schools of Hillel and Shammai. The Jews had a proverb on the matter that said, “Hillel loosed what Shammai bound.”[3] In terms of moral and biblical interpretation, both rabbis and their schools had their faults. Neither one fully comprehended the ultimate plan of God for husband and wife. However, in this case, Jesus accepted the divorce regulations of the School of Shammai but also demonstrated forgiveness that this school generally failed to demonstrate.

Even though Judaism esteemed women higher than in neighboring cultures, women were confronted with four major disadvantages.

- Often but clearly not always, they were looked upon as an object of possession rather than a person of worth. There are numerous writings that support both viewpoints on this subject.

- Obtaining an exit out of a brutal marriage was difficult, although not impossible.

- The acquisition of a divorce by a man was far too easy (see below). Such divorces were based on a very broad interpretation of Deuteronomy 24:1.

- Once a woman was divorced, employment opportunities were almost non-existent. Single women, such as widows, often lived in poverty.

According to some rabbis, the reasons some rabbis gave men for a divorce included the following,

- “Spinning” in the streets, which meant speaking to men in public.[4]

- Being in public with her head uncovered, or allowing her hair to be visible. Only in a wedding procession could she have her head uncovered.[5] Women were expected to have their heads covered in such a manner that their hair was not seen. This is most likely the reason why the Apostle Paul said that women should have their heads covered (1 Cor. 11:5-6) when he wrote to the church in the morally corrupt city of Corinth.

The divorce decree protected the rights of the woman so that she could remarry and her children would not be considered illegitimate.[6]

All are required to write a bill of divorce, even a deaf mute, an imbecile, or a minor. A woman may write her own bill of divorce and a man may write his own quittance, since the validity of the writ depends on them that sign it.

Mishnah, Gittin 2.5

No bill of divorce is valid that is not written expressly for the woman.

Mishnah, Gittin 3.1

The position held by Jesus is similar to that of the orthodox rabbinical School of Shammai, as recorded in the Mishnah.[7] The following passage reflects the differences between the two major theological schools.

The School of Shammai says: A man may not divorce his wife unless he has found unchasity in her, for it is written, “Because he has found in her indecency in anything.”

Mishnah, Gittin 9:10

The School of Shammai held that the phrase “because he found some uncleanness in her” from Deuteronomy 24:1, was a figure of speech meaning she was guilty of adultery.[8] However, the School of Hillel said the phrase meant anything and everything that the husband did not like or approve of.

And the School of Hillel says, “[He may divorce her] even if she spoiled a dish for him, for it is written, “Because he has found in her indecency in anything.”

Mishnah, Gittin 9:10

In modern terms, it could be said that Rabbi Hillel instituted a form of no-fault divorce.

(If a man said) “Konam! If I marry the ugly woman such-a-one, though she was indeed beautiful; or the black woman such-a-one, though she was indeed white; or the short woman such-a-one, though she was indeed tall; she is (yet) permitted to him not because she was ugly and became beautiful, or black and became white, or short and became tall, but because it was a vow made in error.”

Mishnah, Nedarim 9.10

Both Shammai and Hillel were Pharisees, and that is why the following incident occurred:

Some Pharisees approached Him to test Him. They asked, “Is it lawful for a man to divorce his wife on any grounds?”

Matthew 19:3

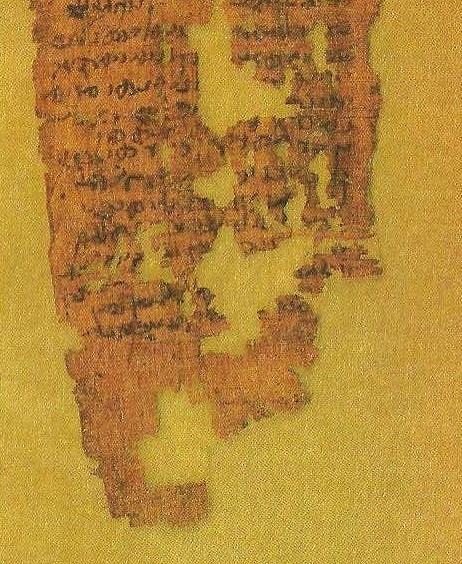

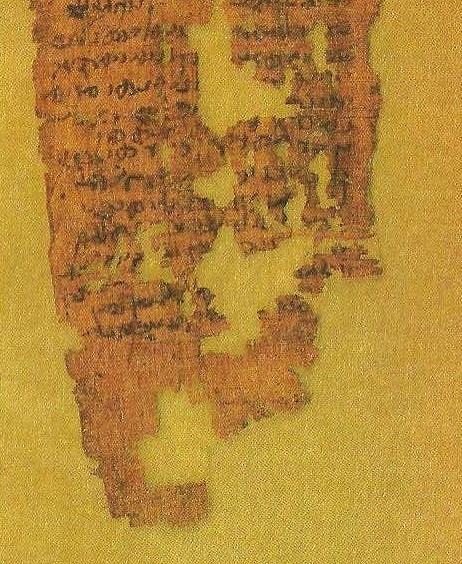

08.02.03.A. A FIRST CENTURY BILL OF DIVORCE. This bill or certificate of divorce,[9] written in Aramaic on papyrus, was discovered in one of the caves in the Judean hills. This type of legal document was to protect the woman when the marriage ended (see translation below).

Divorce documents described any future payments that were due by the husband, although terms varied. The rabbis agreed that if a divorce document did not protect the wife, it was not a legal contract. The first century bill of divorce reads, in part, as follows,

Lines 1-11: On the first of [the month of ] Marheshvan, year six, at Masada.

I, Yehosef [Joseph] son of Naksan from [ ]h, living at Masada, of my own free will, do this day release and send you away, Miriam daughter of Yehonantan [Jonathan] from Nablata, living at Masada, who have, until now, been my wife, so that you are free on your part to become the wife of any Jewish man you may wish. Here you have from me [literally, from my hand] a bill of divorce and a writ of release. Likewise, I give back [to you the whole dowry], and if there are any ruined or damaged goods or [ ]n, I will reimburse you fourfold, according to the current price. Furthermore, upon your request, [if lost], I will replace this document for you, as is appropriate.

Lines 12-25: [A repetition of the text is almost identical wording.]

Lines 26-29: {Signed} Yehosef son of Naksan, by his own hand

Eliezer, son of Malkah, witness

Yehosef, son of Malkah, witness

Eleazar, son of Hananah, witness

Divorce Decree (Courtesy of the Shrine of the Book, Israel Museum).[10]

Josephus not only confirmed the high frequency of divorces, but also that the divorce decree was for the protection of the wife, so she could remarry. He stated that,

He that desires to be divorced from his wife for any cause whatsoever (and many such cases happen among men), let him in writing give assurance that he will never use her as his wife anymore; for by this means she may be at liberty to marry another husband.

Josephus, Antiquities 4.8.23 (253)

It is evident that the right to remarry was understood and was not a matter of debate as it is in some Christian denominations today. Furthermore, neither Jesus nor the Apostle Paul prohibited remarriage even though they knew this practice was evident.

“Except in a case of sexual immorality.” Twice in his book, Matthew refers (5:32 and 19:9) to a reason for which divorce is permissible. It is interesting to note that in Mark 10:2-12, the only person initiating the divorce and subsequently remarrying is charged by Jesus as committing adultery. While God condemns divorce, Jesus shows that the Law is a demonstration of God’s willingness to accommodate Himself to human frailty and failure.

Ironically, the rabbis of the School of Hillel were morally right, but exegetically wrong, while those of Shammai were morally wrong, but exegetically right. Shammai actually recognized the “spirit” of the Mosaic Law, while Hillel was right only in that an opening for divorce was permitted.[11] Since marriage is a covenant, there is little wonder then that Jesus went from the marriage issue directly to honesty without swearing or the taking of oaths. In the meantime, the Essenes believed divorce was considered illicit under all circumstances.[12]

08.02.03.Q1 Did polygamy exist in the first century?

Beginning during the time of the Judges, the practice of polygamy slowly decreased, although the three famous kings (Saul, David, and Solomon) were not the best examples of that trend. Wherever there were multiple wives there were multiple problems. By the Inter-Testamental period, the book of Tobias refers only to a husband-wife family, a pattern well established by the Old Testament prophets.[13] The prophet Ezekiel portrayed the husband-wife relationship as being similar to Israel-God in the allegory of Ezekiel 16.

By the first century, polygamy was rare, but not unheard of. Men, not women, had the approval of historic tradition to have more than one spouse at any given time. Polygamy was rarely practiced throughout the Talmudic Period until it was officially banned in A.D. 1240.[14] (As will be later explained, it was practiced in the 17th century Yemen and was a topic of discussion in 1806 in France.) But evidently it was common enough that Josephus addressed it.

If anyone has two wives, and if he greatly respects and be kind to one of them, either out of his affection to her, or for her beauty, or for some other reason while the other is of less esteem with him, and if the son of her that is beloved be the younger by birth than another born of the other wife, but endeavors to obtain the right of primogeniture from his father’s kindness to his mother, and would thereby obtain a double portion of his father’s substance (inheritance), for that double portion is what I have allotted him in the laws.

Josephus, Antiquities 4.8.23 (249)

Obviously there were Jewish men with two or more wives, or the historian would never have written about the subject. He then continues in section 4.8.23 with the complexities of marriage and divorce. As for him, his first wife was killed at the siege of Jotapata, his second wife deserted him, and after he retired in Rome to pursue a literary career, he married his third wife.[15] But some scholars believe he had four wives in serial marriages,[16] who gave him a total of five sons.[17]

Under Roman law bigamy and polygamy were strictly forbidden,[18] although adultery was not. Nonetheless, the practice continued and in some Islamic countries, such as Yemen in the 17th century, persecution and death at the hands of Muslims was so severe that Jewish men had to take on multiple wives, (including widows) to keep the Jewish race alive and prevent Jewish women from becoming impoverished homeless outcasts. However, since the Second Temple Period the practice was discouraged, unless “the husband was capable of properly fulfilling his marital duties toward each of his wives.” But local customs varied and many katuvah (marriage deeds) forbade a future second wife.[19] Yet examples of polygamy are as follows:

- Amazingly, the Mishnah records that a Jewish king could have a limit of 18 wives.[20] This is an interesting limitation since Israel did not have a king at the time the Mishnah was written, but was under the control of the Romans who forbade the practice. Without question, the codex of the Oral Law applied to Jews living outside of the Roman domain.

- Rabbinic writings do record one interesting incident of a rabbi, of all people, who had two wives. The Jerusalem Talmud has the account of a certain Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus who married his niece in his later years.[21] The Babylonian Talmud preserved the same account (Sanhedrin 68A) with additional details and identifies Rabbi Hyrcanus’ wife as Imma Shalom, the daughter of Rabbi Simeon ben Gamaliel, and she outlived her bigamist husband.[22] His second wife was also his niece. It is unclear if he was excommunicated for bigamy or being married to his niece.[23] However, his actions did not appear to conflict with the School of Shammai,[24] but the social discord this caused evidently discouraged others from the practice, as there is no further written evidence of Talmudic sages who engaged in this practice.[25]

- A well-known Jerusalemite by the name of Tobiad Joseph had two wives.[26]

- Alexander Jannaeus of the second century (B.C.) had several wives, one of whom was his “chief wife.”[27] Since he was the monarch of the Holy Land, maybe he is the reason the Mishnah later recorded that a king could have up to 18 wives.[28]

Those who believe that polygamy disappeared need to reconsider their position.[29] While the provisions of the typical katuvah are credited to the great reduction of polygamy, it did not eliminate it.[30] However, by the first century, the issue was not polygamy, but serial marriages – that is one wife after another. That is why divorce was a topic of heated debate. This subject continued into the Church Age. The church fathers, Cyril of Jerusalem and Jerome, made these comments concerning second marriages:

And those who are once married – let them not hold in contempt those who have accommodated themselves to a second marriage. Continence is a good and wonderful thing; but still, it is permissible to enter upon a second marriage, lest the weak might fall into fornication.

Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures[31]

What then? Do we condemn second marriage? Not at all; but we praise first marriages. Do we expel bigamists from the Church? Far from it; but we urge the once-married to continence.

Jerome, Letter to Pammachius[32]

In the Apostle Paul’s letter to Timothy, he said that a pastor/elder should be the husband of one wife (1 Tim. 3:2). A number of evangelical denominations today interpret this to exclude anyone from a ministry position who is in a second marriage. The position is held because it is believed that the divorce is still a marriage; that God does not honor the divorce. Furthermore, these evangelicals often believe that bigamy was outlawed in the first century Judaism. However, the comment by Jerome, “Do we expel bigamists from the Church?” clearly reveals that the church accepted men with two wives, but Timothy said they were not qualified to serve in the church. Bigamy was technically legal but rarely practiced.

Josephus recorded the account of King Izates of Adiabene (reigned A.D. 35-60) who ruled the small semi-independent kingdom of Adiabene. He and many in his family had converted to Judaism as the result of Jewish merchants who told them about the God of the Jewish people and the Jewish religious traditions. As king, he even underwent the rite of circumcision.[33] When he felt his kingdom was threatened by the Parthians, he placed ashes on his forehead and told all his wives and children to call upon God for help. The account reads as follows:

He (Izates) knew the king of Parthia’s power was much greater than his own; but that he knew also that God was much more powerful than all men. And when he had returned him this answer, he betook himself to make supplication to God, and threw himself on the ground, and put ashes upon his head, in testimony of his confusion, and fasted together with his wives and children.[34] Then he called upon God.

Josephus, Antiquities 20.4.2 (89)

The Lord apparently heard and answered his prayer for help and mercy, because he remained undefeated and his kingdom prospered. When he died, he had 48 sons and daughters, but the number of wives is unknown.[35] A point of interest is that his mother, Queen Helena, after she converted to Judaism, built a palace in Jerusalem so she could worship God in the Jewish temple. When famine struck the Middle East in A.D. 45, the same famine of Acts 11:28-30, she provided funds to purchase food for the needy. Eventually, when she and her two sons, Izates and Monobasuz II died, their bones were buried in a tomb in the Hinnom Valley.[36] Josephus and the Jewish writings praised them for their contributions in time of dire need.[37]

The irony of the acceptance of Queen Helena is that her husband, King Monobazus I, was also her brother. Her two sons were essentially children of incest. Yet, in spite of all the laws of purity, once she and her family accepted Judaism, the Pharisees and Sadducees no longer had any issues with her – unlike Jesus with whom they had constant disagreements.

Finally, as previously stated, it is worth repeating that Hillel was clearly influenced by the Hellenistic trends of the time. In the early days of the Roman Republic, marriage was considered sacred and divorce was unknown – an amazing tradition for a pagan culture. However, with the advent of Hellenism and the lax attitudes of marriage by the Greeks, the Romans followed. Hillel accepted some Greek ideas of marriage and restructured these theologically to fit the Jewish mindset. Has something similar happened in Western culture today?

[1]. Miriam was so angry because Moses married a black woman, that God punished her by making her white with leprosy. Clearly God demonstrated His anger at racism. Eventually she was healed.

[2]. A few scholars do not agree with this interpretation and say that Zipporah and the Cushite woman was one and the same person.

[3]. Cited by Farrar, The Life of Christ. 349.

[4]. Mishnah, Ketuboth 7.6; Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 359-61; For further study, see Chapter 18 “The Social Position of Women” in Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus.

[5]. Mishnah, Ketuboth 2.1.

[6]. Mishnah, Gittim 9.4; Among the two major theological schools in Jerusalem, the School of Shammai was very strict while the School of Hillel was very relaxed (i.e. “no-fault” divorce permitted) concerning the issuance of a divorce decree.

[7]. Mishnah, Gittin 9:10. For further study, see Kister. “The Sayings of Jesus and the Midrash.” 39-50.

[8]. Wigoder, “Divorce;” See also Josephus, Antiquities 4.8.23.

[9]. For a typical bill of divorce format, see also Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica. 2:124-25.

[10]. Ward, Kaari, ed. Jesus and His Times. Reader’s Digest: New York, 1987, 76.; Translation by Biblical Archaeology Review 22:1 (Jan/Feb, 1996) 17. For a further study, see J.T. Milik in Discoveries in the Judean Desert. P. Benoit, J. T. Milik and R. De Vaux, eds. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1961), 2:1-4-109, plates 30-31.

[11]. Farrar, Life of Christ. 306-07.

[12]. Dead Sea Scrolls: CD 4:21; 11Q Temple 57:17-19.

[13]. Trutza, “Marriage.” 4:92.

[14]. “Bigamy and Polygamy” Encyclopedia Judaica CD-ROM 1977.

[15]. Wilkins, “Peter’s Declaration concerning Jesus’ Identity in Caesarea Philippi.” 357; Farrar, The Life of Christ. 350.

[16]. Farrar, The Life of Christ. 348-49.

[17]. Grant, The Ancient Historians. 253.

[18]. http://www.ancient.eu/Cleopatra_VII/. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

[19]. Falk, Jesus the Pharisee. 88-89, 99, 106-07. The marital contract is further described in 04.03.03.A and 08.02.01.

[20]. Mishnah, Sanhedrin 2.4. However, the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 21a, gives a greater number, 24. Clearly there was disagreement among the rabbis even though this was a hypothetical issue. See also Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 369.

[21]. Jerusalem Talmud, Yevamot 13:2; Avot D’Rabbi Nathan, Ch. 16.

[22]. This irony of this matter is that this Gamaliel is believed to have been the grandson of Hillel, the constant opponent of Shammai.

[23]. Babylonian Talmud, Bava Mezia 59B; Yet it is interesting that due to heavy persecution by Muslims, Jewish men in Yemen, as late as the19th century, had to take more than one wife because so many men were murdered. In this case, polygamy preserved the Jewish race.

[24]. Jerusalem Talmud, Betsah 1:4

[25]. Falk, Jesus the Pharisee. 53, 100-02.

[26]. Josephus, Antiquities 12.4.6 (186-90).

[27]. Josephus, Antiquities 13.14.2 (380); Wars 1.4.6 (97).

[28]. Mishnah, Sanhedrin 2.4. However, the Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 21a, gives a greater number, 24. Clearly there was disagreement among the rabbis even though this was a hypothetical issue. See also Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 369.

[29]. Johannes Leipoldt in Jesus und die Frauen, Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1921 (reprint 2013), 44-49, gives many more examples in his notes. See also Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 93.

[30]. An interesting event occurred in the early nineteenth century, which challenges conventional Christian opinions that monogamy was the standard practice in the first century. When Napoleon conquered Europe, the Jews were encouraged to re-establish their ancient court system, the Sanhedrin. Because of this decree, in 1806 Jews assembled to discuss a number of pressing problems. Of the many questions discussed, the first one was, “Is it lawful for Jews to marry more than one wife?” While the response was negative, it revealed that it was still an issue in various places. For example, in the 11th century Jews in Worms, Germany practiced bigamy. And in 17th century Yemen, the Muslims killed so many Jewish men that the surviving Jewish men who were married previously, then married the widows so these women would not become destitute.

[31]. Thomas, The Golden Treasury of Patristic Quotations: From 50 – 750 A.D. 175.

[32]. Thomas, The Golden Treasury of Patristic Quotations: From 50 – 750 A.D. 175.

[33]. Josephus, Antiquities 20.2.3-4.

[34]. Ashes placed on the forehead were cultural signs of deep grief and mourning, and in this case, sincere appeal to God. Vine, “Ashes.” Vine’s Complete Expository Dictionary. 2:39.

[35]. Schalit, “Izates II.” Encyclopedia Judaica CD ROM; Notley and Garcia. “Queen Helena’s Jerusalem Palace,” 28-30.

[36]. This tomb was incorrectly identified as the “Tomb of the Kings.” See Notley and Garcia. “Queen Helena’s Jerusalem Palace,” 28-39 for historical and archaeological information.

[37]. Josephus, Antiquities 20.2.1-20.4.3; Mishnah, Yoma 3.10.

08.03.00.A. JESUS TEACHES PRINCIPLES OF LIFE. Illustrated by James Tissot. 1878.

08.03.00.A. JESUS TEACHES PRINCIPLES OF LIFE. Illustrated by James Tissot. 1878.