04.04.06 Mt. 2:1-8 Jerusalem (c. 4-2 B.C.)

THE MAGI SEEK JESUS

1 After Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judea in the days of King Herod, wise men from the east arrived unexpectedly in Jerusalem, 2 saying, “Where is He who has been born King of the Jews? For we saw His star in the east and have come to worship Him.”

3 When King Herod heard this, he was deeply disturbed, and all Jerusalem with him. 4 So he assembled all the chief priests and scribes of the people and asked them where the Messiah would be born.

5 “In Bethlehem of Judea,” they told him, “because this is what was written by the prophet:

6 And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah,

are by no means least among the leaders of Judah:

because out of you will come a leader

who will shepherd My people Israel.”

7 Then Herod secretly summoned the wise men and asked them the exact time the star appeared. 8 He sent them to Bethlehem and said, “Go and search carefully for the child. When you find Him, report back to me so that I too can go and worship Him.”

Previously, the residents of Bethlehem must have been shell-shocked when the shepherds told them of what they had heard and seen. A child born to unwed parents caused quite a stir, yet the reports from the “Sanctified Shepherds of the Seed of Jacob” made people stop and wonder what God might be doing. Only time would tell. However, the Bethlehemites would be in for a second surprise – the visit by the Parthian magi and their escort of soldiers and servants. Not only were they wondering what was going on, but so did those in the Herod’s palace. Even though Herod was in the last stages of his life with a disease that was slowly and miserably rotting away in his bowels, he still feared that someone would challenge his throne.

The political dynamics at this point were phenomenal and, therefore, a brief historical review is required. While the Roman Empire was expanding across the Mediterranean and into parts of Europe, the Parthian Empire was expanding in the East. Today’s Israel and parts of Jordan were the frontiers of these rival empires.

In 63 B.C. the Romans came down from Damascus and took control of the Jewish lands. But in 53 B.C.[1] when the Romans attempted to expand eastward, they were soundly defeated (see 03.05.18). In retaliation, the Parthians invaded Jerusalem and held it until Antipater, the father of Herod the Great, chased them out.[2] A few years later, the Jews rebelled, but by then Herod was in command and he ruthlessly massacred thousands, quickly drove out the remaining Parthians, and restored order. Since he was somewhat of a psychopath, he was always fearful of an attempted overthrow of his kingdom and suffered fits of depression.

Therefore, when the Parthian magi came, he most certainly reflected on events that occurred in the early years of his reign. Herod’s lack of concern can only be attributed to the fact that he had a massive Roman army at his disposal and the magi and their protective escort and caravan could have been easily slaughtered if needed. While there is no mention of him sending out any spies to observe them, although his psychological profile and the recorded events of his life by Josephus suggest that he was aware of their actions and travels until they slipped out.

04.04.06.Q1 How does the prophecy in Matthew 2:6 agree with Micah 5:2?

The apparent conflict arises because part of Matthew’s quotation is found in Micah but another part is found in 2 Samuel 5:2. The answer lies in understanding how first century rabbis interpreted Scripture; a matter of first century hermeneutics.

Video Insert >

04.04.06.V Insights into Selected Biblical Difficulties. Dr. Joe Wehrer discusses Jewish hermeneutics to clarify three so-called biblical conflicts in the gospels. (11:07)

Rabbis often took the liberty to cite quotations given by two prophets, but gave the credit to the better known prophet. Therefore, Matthew’s prophecy does agree with the Old Testament because he used the common method of quoting Scripture. He presented a paraphrase of Micah 5:2 with emphasis on the small village of Bethlehem as the fulfillment of prophetic words.[3] Matthew said that the smallest village of Judea was from where God’s greatest gift came in fulfillment of Micah’s prophecy. NOTE: Concerning Matthew 2:6 and Micah 5:2, please see the video “Insights into Selected Biblical Difficulties” 04.04.06.V.

“Wise men from the east.” The phrase in Greek is magoi apo anatolon, which is where translators obtained the word magi. This phrase gives one of the most dynamic insights into the religious and political setting at the time of Christ. Few phrases in the New Testament have provided more fuel for debate than this one. Hence, special attention is given to it here as scholars have often discussed the following question:

04.04.06.Q2 Could the magi have come from Arabia, rather than from Parthia in the east?

In Hebrew, the word east not only refers to a compass direction, but also means the rising, with an obvious reference to the rising of the sun.[4] There are several points to consider in this study:

- If the Scripture verse had only that word – east – then the wise men could have originated anywhere east of the Jordan River.

- However, the word “magi” places the focus on the ancient Babylonian Empire.

- Consequently, the word east is limited to ancient Babylon, later known as Persia and Media (Ezek. 25:4; Isa. 2:6), but in the first century was part of the Parthian Empire — an enemy of the Rome.[5] (Although some scholars have suggested that Isaiah 60:6 implies Arabia as the point of origin.)[6]

- The Magi probably were from Parthia, but traveled through Arabia on their way to Jerusalem and Bethlehem.

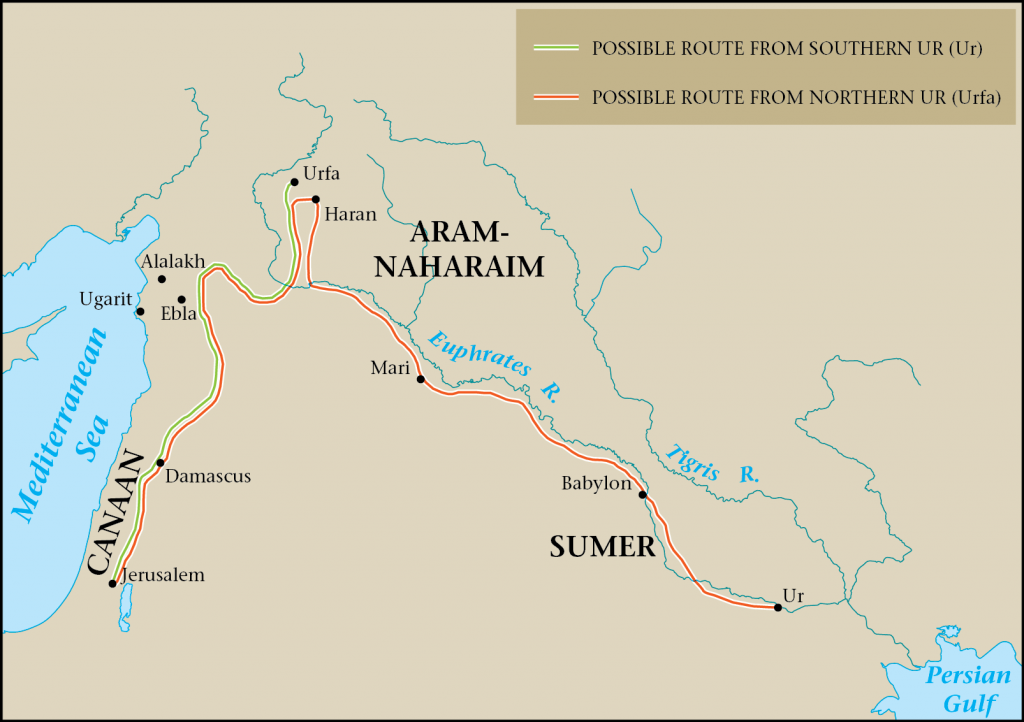

Most scholars believe the magi traveled from Ur or Babylon northwest along the Euphrates River, the westward and southwest to Damascus and on to Jerusalem. They most likely avoided the searing hot desert and traveled within the Fertile Crescent[7] along a road known as the Via Maris.

04.04.06.Z A MAP OF THE POPULAR ROUTE FROM UR AND BABYLON TO JERUSALEM. The ancient road the magi followed was probably the same one in the Fertile Crescent that Abraham had used centuries earlier. It was the most feasible route to avoid the massive northern section of the Arabian Desert (today part of Jordan) that lies directly between Babylon and Jerusalem. Whether they came from Babylon, Ur, or elsewhere, they could not travel in a straight line from east to west because there were no sources of water in that area of the desert. Courtesy of International Mapping and Dan Przywara.

However, there seems to be a different opinion concerning their origin among some historic sources. Justin Martyr said in his apologetic book that,

The wise men from Arabia came to Bethlehem and worshiped the child and offered to him gifts [of], gold and frankincense and myrrh.

Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 78[8]

Apparently Justin Martyr was not the only one who held this opinion, Tertullian and Clement of Rome made similar comments and may have used Martyr as their source.[9] However, this priestly-kingly class of men did not function in Arabia. Therefore, Arabia was probably not their home or point of origin, but part of their travel itinerary. Isaiah also gave prophetic evidence that the magi would come from Arabia, but again that does not mean they originate from there. The passage reads as follows:

Caravans of camels will cover your land — young camels of Midian and Ephah — all of them will come from Sheba. They will carry gold and frankincense and proclaim the praises of the Lord.

Isaiah 60:6

Notice that the passage indicates that young camels came from Midian and Ephah. These were two Arab tribal areas in northern Arabia. The narrative continues to say that people from Sheba would also come – Sheba is from the southern region of Arabia from where came the famous queen of Sheba with a huge amount of gold (1 Kgs. 10:2). Southern Arabia was known for its fine quality of frankincense.[10] There are three noteworthy thoughts concerning this matter:

- If the magi came from Arabia, that would explain why Herod the Great was not very concerned about them, since he was an Idumean, a tribe that was closely related to the Arabs and eventually became part of the Arab nation.

- On the other hand, very little is known about the office and function of magi in the Arabian world. Some believe they hardly existed, if at all. There is no mention of them in the Qu’ran other than possibly a degrading comments about a religious group known as “Magians,” (Sura 22:17) which is coupled to the Jews, Christians, and a group known as the “Sebeites.” [11] If there ever were any magi in Arabia, they certainly did not have the status, power, wealth, or influence as did their counterparts in Parthia. If the magi did originate from Arabia, then why is there no evidence of such a kingly class of men?

- It has generally been assumed that the magi came from Parthia by way of the popular northern route – traveling along the Euphrates River, then turning westward toward Damascus, and then turning southwest toward Jerusalem (see map 04.04.06.Z). However, if they came from Parthia by way of a southern route through Arabia, it would be natural for Justin Martyr, Tertullian, and Clement of Rome to say that they came from Arabia even if that was not their point of origin.

Finally, the magi are known to have visited at least one other monarch. In the year A.D. 66 they traveled to Naples to honor Nero and, for an unknown reason, when they left, they traveled home by way of a different route.[12] After this they departed from history. There is no mention of them in Scripture, secular history, or apocryphal tradition. It is generally believed they simply vanished because, in the course of time, the needs of kings changed. But their generosity created the tradition of a Christmas gift exchange that is well known throughout the Western world and beyond.

Concerning Isaiah 60:6, only a few scholars believe Isaiah’s prophecy refers to the magi; most believe this passage refers to a future time and, therefore, cannot be connected with the magi of the first century. So their origin remains a veiled mystery known only to God, but the probability is very high that they came from Babylon.

“Where is He who has been born King of the Jews?” The magi did not ask if the king had been born, but where he was born. This statement of confidence must have shocked Herod, yet he snubbed them and failed to personally pursue the report. His lack of courtesy was no doubt shocking, as the magi were official ambassadors of the Parthian government.

04.04.06.Q3 Was the star of Bethlehem really a star?

The magi said they came “for we saw His star in the east.” This phrase has been fuel for microanalysis, debates, and criticism. Several opinions of the “star” are presented in this study, followed by the opinion of this writer. But first notice the unique features of the star:

- It moved erratically compared to other stars; east to west, then north to south

- It appeared and disappeared at least twice.

- It apparently was not visible to everyone

- It literally came close to a house in Bethlehem and hovered over it.

- It was seen only be a selected few people

- This star is referred to a pronoun “His.”

Obviously this was not a natural heavenly body commonly referred to as a “star.” While it was observed in the east and traveled westward, there were never any straight-line east-west roads. In fact, the terrain of the land would make such a road impossible and, furthermore, there were no rivers, wells, or other water sources in the vast northern section of the Arabian Desert (as it was called then) directly east of Jerusalem. Therefore, when the magi came from the east and traveled west, they most certainly followed a star that took them on the road that circumvented the desert. Incidentally, it appears that only they – the magi – saw it. It moved, stood still, changed direction, evidently was over the city of Jerusalem, changed direction from westbound to southward, hovered over a house, and still no one else noticed it. How strange!

Yet scholars have often struggled to connect the star of Bethlehem with astronomical alignments. The most popular interpretation of the “star” is that it was a planetary alignment of Jupiter and Saturn, which occurs every 805 years. Since the Babylonians recorded major astrological and political events, they left writings of an interesting luminary event that were discovered in 1925. In that year, a German researcher, P. Schnabel, translated clay tablets from the School of Astrology in Sippar, Babylon.[13] These tablets had a record of a unique five-month alignment of planets (Jupiter and Saturn) in the constellation Pisces, in a year that has been reckoned to 7 B.C. Modern science has confirmed that these two planets were closely, but not perfectly, aligned in May, October, and November of that year. However, the alignment was only for a few days and then the planets drifted apart.[14] There never was a single bright light, even when the planet Mars joined this duet in the following year. To accomplish this feat, the planets would have left their natural orbit and led the magi for two months around the northern edge of what was then called the Arabian Desert (today’s modern Jordan). To add doubt to this interpretation, there is no evidence that the magi believed such astrological conjunctions was “a star,” meaning, they would not have called the planetary alignment “a star.” Since then a number of astronomers have argued against any planetary alignment because Jupiter and Saturn were never close enough to be seen as a single light.[15]

Another possibility is the comet that appeared between March 9 and April 6 of the year 5 B.C. and lasted for more than seventy days.[16] Matthew 2:7 indicates that the new star had just “appeared” and, therefore, was not a part of the celestial bodies that were normally observed. Its speed of travel was different from other starry lights (Mt. 2:2, 9) and, in a rather unusual move, the star stopped “over the place where the child was” (Mt. 2:9). At this point, a comment by a Roman historian may add to the understanding of the word “stopped.” Dio Cassius described Haley’s comet in 12 B.C. by stating that “the star called comet stood for several days over the city (Rome).”[17]

It is the opinion of this writer that this so-called “star” of Bethlehem was not a literal star, but either a divine light or an angel. Such luminary figures are not considered unique to the Scriptures and would have been seen only by those whose eyes were opened by the grace of God. The Israelites were led out of Egypt by a “pillar of light” (Ex. 13:22) and the Apostle Paul encountered a “light from heaven” (Acts 9:3). The movement pattern of the so-called star and its position over a specific house eliminate the possibility of a true physical star (although that is how it appeared) and permit for only two divine possibilities:

- It was either an angel of light (cf. Num. 24:17; Job 38:17; Ps. 104:4; Heb. 1:7; 2 Pet. 1:19; Jude 13; Rev. 1:20; 2:28; 9:1; 12:24), or

- It was the Shekinah Glory of God to the Gentiles.

This interpretation reconciles a problem (of changing movement and position) that other interpretations avoid, that is, the “star” traveled from Babylon in the east and went hundreds of miles westward to Jerusalem. From there it turned about ninety degrees and went due south seven miles to Bethlehem. No starry or planetary object is capable of traveling in this manner. The unusual light then came close enough to the earth so as to identify a specific house without incinerating it, the village, or the earth. This issue has also been avoided by those who attempt to identify a star, comet, or planetary combination. While God, who created the heavens, could certainly have changed the natural course of a single star, He probably had a different purpose in mind. The movement of the heavenly light is far more descriptive of an angel or the Shekinah Glory of God rather than a celestial ball of fire, a/k/a star.

As to how the magi became fascinated by the starry light, there are several influential facts to be considered.

- Centuries earlier, Balaam was also an astrologer from the Babylonian Court (Deut. 23:4). In his account, the star was identified as the scepter of kingship (Num. 24:17).

- The Israelites who were taken by the Assyrians eastward kept the messianic hope alive and told others about it.

- The prophet Daniel was from a priestly class in Jerusalem, but was taken captive to Babylon where King Nebuchadnezzar appointed him to be the head of the religious class. After his encounter in the lion’s den, everyone listened when he spoke. By the inspiration of God, Daniel predicted the number of years until the first coming of the Messiah (Dan. 9:24-27), and his ability qualified him to be among the Babylonian astrologers.

However, the magi of the Babylonian court (6th century B.C.), who later held the same position in the Parthian Court (1st century), did not have Micah’s prophecy concerning the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem (Mic. 5:2). Hence, when the magi were looking for the newborn king, they naturally went to the king’s palace in Jerusalem. It was there where they learned of the passage in Micah and went a few miles south to the village of Bethlehem.

Finally, the Greeks and Romans had always considered that significant events, as well as the births and deaths of great men, were symbolized by the appearance or disappearance of heavenly bodies—a custom that has transitioned to modern times. They had heard of the Balaam who said that a star would arise from the east, and this star would be significant to the coming ruler of the world. Amazingly, only a century after Jesus, the celebrated Rabbi Akiva (Akiba)[18] gave a messianic pretender the name “Son of the Star.” That pretender, Simon bar Kokhba, in A.D. 132 led a rebellion against the Romans, but the Romans defeated him.[19]

“The prophet.” Matthew used the singular form (Gk. Prophetou) even though he made reference to the words spoken by the prophet Micah (5:2).[20] The Jews in the Holy Land had access to Micah’s prophecy, but the Babylonian Jews did not.

“As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him.” What Herod was really saying, “as soon as you find him, report to me, so that I may go and kill him.” His reign includes a long history of murders of friends and various family members.[21]

04.04.06.Q4 Who were the wise men/magi?

The Greeks designated the Persian priests as “magi,” and the Persian state religion of Zoroaster as “magianism.”[22] Their focus was to study the starry skies for the coming of a savior. It was Cyrus who first established magianism in Persia, and the powerful and influential group men were known as “magi.”[23] The rabmag, or head of the magi, was first mentioned in the Bible in Jeremiah 39:3 and in Daniel 2:2 and 4:7.[24] The magi (magoi) were the proverbial “wise men” from a royal court of the Parthian Empire, although other kingdoms such as China, India, and possibly Arabia, also had magi. They were knowledgeable in mathematics, the sciences, astronomy as well as astrology. More importantly, they were advisors to kings and held positions of educators and ambassadors. Kings ruled over the people but the magi directed the kings. No king went to war without first consulting them. The magi of the biblical text are believed to have been originally from Media and Persia, which was within the expanding Parthian Empire. So they clearly were no strangers to the Jewish people. However, over the centuries the definition of the name changed with an emphasis on astrology, or Oriental soothsayers (as in Acts 12:6).

One of their primary functions was to insure transition in government. They were responsible for educating the children of the royal court and. therefore, were called the king makers, but they were not kings.[25] They also re-educated the nobility of conquered nations, which put them in direct contact with Daniel and his comrades. They taught a wide range of subjects, including mathematics, astronomy, astrology, the sciences, divination, military skills, and magic, but mainly religion.[26] Their status of royalty was not only acknowledged by the early church, but was also predicted by the prophet Isaiah (60:3).

The magi served their kings in various capacities from the cradle to the grave. When a son was born into a royal home, whether at home or in a neighboring country, it was customary for the magi to honor that family. It was for this reason they traveled first to the home of Herod the Great, since this was obviously the most likely place where the son of a king would be born.[27] It is an interesting point of history that these magi, who studied the stars and were looking for a messiah, were led to the real Messiah by a star/angel of divine appointment. But the temple Sadducees, who supposedly represented the people before God, did not want to have anything to do with this infant born in Bethlehem, a paradox well documented throughout Matthew’s gospel.[28]

The magi were hardly the men often depicted on modern Christmas displays. The usual image of the magi is three men dressed as kings or knights on camels who arrived alone, dressed in fine colorful clothing and having huge chests of gifts. They were of such a high order that they never rode camels, but only on horses, ideally the world-famous Arabian horses. Ordinary and wealthy people of the Babylonian, Persia, and later Parthia, rode donkeys, mules, and camels. Long distance haulers of merchandise used camel caravans. Note the following from Parthian history:

- When the Persian King Cyrus II (reigned 550-530) united the Persians and Medes to defeat the Babylonians in 539,[29] his processional march into Babylon on a horse was quite typical for a victorious monarch.

- The Parthians had two types of cavalry: the heavy-armed and armored cataphracts[30] and the light brigades of archers who were skilled horsemen.[31]

Horses were more common in the semi-arid deserts of antiquity than many believe. The magi were exclusive and unique. Not only did they ride horses, but their clothing was entirely white. And they certainly did not arrive alone. Traveling in remote areas was always an invitation to be robbed or murdered, especially if the traveler appeared to be wealthy. They were escorted with an entourage of soldiers, cavalry, food and water supplies, and comfortable sleeping tents. They were far too dignified to sleep out under the stars with commoners.[32]

Once they arrived in Jerusalem, they obviously displayed wealth, the power of a foreign government, and a degree of mysticism since they were following what they perceived to be a star. What kind of effect did they have on those who saw them arrive in Herod’s palace in Jerusalem? It is unknown, but the mystery that remains is this: Since the Parthians invaded and controlled Jerusalem briefly in the year 40 B.C., why was Herod the Great apparently so complacent when they arrived? This question remains unanswered.[33]

Finally, the names of the magi have been lost in history. Yet it seems that every few years there is a “recent re-discovery” in the Western media which reveals their identities. One report states that in the 12th century, three skulls were “discovered” by Bishop Reinald in Cologne, Germany, that were identified as being Melchior, Caspar and Balthazar – the magi of the Bethlehem.[34] Unfortunately, church history is full of absurd traditions by fanciful writers.[35] This matter is mentioned simply because there are no reliable ancient sources to verify the claim and, therefore, these names have no historical value.

04.04.06.Q5 Why were the wise men/magi interested in a Jewish Messiah?

By the first century the magi were very much aware of the prophecy recorded in Numbers 24:17 because historically, the Babylonians were eager to learn from other cultures. In fact, the Persian state religion had priests who taught and studied “magianism,”[36] the study of the skies they believed would signal the coming of a savior. Hence, they were looking for a messiah as much as were the Jews. Without question there was a connection between the wise men (magi) of Daniel and the magi who came to honor Jesus.[37]

However, there is another reason why these magi would have had a strong interest in the Jewish messiah. Throughout the ancient Middle East at this time there was a growing frustration among the populous with local monarchs who were puppets of European dominance, first by the Greeks and later by the Romans. These subjugated people were crying to their gods for someone who would deliver them. Archaeologists discovered a fragment which provides evidence that the fourth century B.C. magi had a great disdain for Alexander the Great.[38] And herein is another mystery – why would the agents of royalty – those who subjugate the common people, come to worship One who would free them? Furthermore, when they arrived in Bethlehem, they broke the rules of royal protocol – they, the king makers and ambassadors of the Parthian Empire, knelt down before common Jewish peasants and worshiped an infant child. Wealth and power prostrated itself at the feet of poverty.

While no written documentation concerning their interest has survived the centuries, history reveals some clues that provide answers. The historians, Tacitus, Suetonius, and Josephus, indicated that there was a prevailing belief throughout the ancient Middle East that a powerful monarch would arise from Judea. The relocation of the Jews by the Assyrians[39] and Babylonians, as well as the Jews who decided on their own to relocate to foreign lands, all spread the idea that a global ruler would one day arise in the land of Israel. Note what these historians said,

There had spread over all the Orient an old and established belief, that it was fated at that time for men coming from Judaea to rule the world.

Suetonius Life of Vespasian 4:5

There is a firm persuasion … that at this very time the East was to grow powerful, and rulers coming from Judaea were to acquire [a] universal empire.

Tacitus, Histories 5:13

But now, what did most elevate them in undertaking this war, was an ambiguous oracle that was also found in their sacred writings, how, “about that time, one of their country should become governor of the habitable earth.”

Josephus, Wars 6.5.4 (312)[40]

Since the messianic expectation[41] was well-known throughout the entire Mediterranean area, this may be the reason the Roman Emperor Augustus called himself the “savior of the world.” In the meantime, another well-known figure, the poet Virgil (70-19 B.C.), wrote of the wonderful and prosperous golden age that was about to come in his fourth literary work known as the Fourth Eclogue (published between 42 and 38 B.C.),[42] but also known as the Messianic Eclogue.[43] In light of the common expectation of the time, it is amazing that Herod the Great appeared to be rather indifferent about the unexpected visit by the magi.

Previously, in 605 B.C., the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar captured Jerusalem and relocated Jewish families of royalty and priests to Babylon. These captives included a number of prophets, including Daniel. Because Daniel was of Jewish royalty and nobility (Dan. 1:3), he received three years of instruction by the Babylonian magi prior to his service to the court (Dan. 1:3-5). Eventually he became the chief of the magi (Dan. 2: 4, 10, 12, 48). While in Babylon, he wrote the book that bears his name and includes several insights that pertain to the Babylonians. Some scholars have suggested that Persian historians recorded that Zoroaster, the founder of the Zoroastrianism religion, was a student of the prophet Daniel. Clearly, he had a high level of influence in the Babylonian and Persian halls of government. Some scholars believe that the ancient books of the Zoroaster predicted that the next prophet would be born of a virgin, although it does not indicate who or where that prophet would be born.[44]

It does not indicate that he would be Jewish, and furthermore, John the Baptist was the next prophet, not Jesus. It is interesting, however, to see that so many people groups had a concept of a messianic figure that was expected to perform great feats – even though those messianic figures were all sculptured within various cultural and religious frameworks.

Daniel 4 records that the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar had a horrific dream and none of his magi could give him the interpretation, even after being threatened with death. But it was Daniel, the headmaster of the Babylonian school of astrology-astronomy (Dan. 4:9), who was given the interpretation by God. When he explained the dream to the king, he saved not only his own life, but also those of the court magi. Consequently, he was highly respected and appreciated, and others carefully listened to him.

Furthermore, the event of Daniel in the lion’s den left a profound impact on the royal court and beyond – one that lasted for centuries. Just as Balaam was a prophet whose reputation lasted for centuries (see 03.01.05.A), so likewise did Daniel’s reputation. In the ancient world there were many prophets and many aspiring prophets, but none stood the test of a den of lions. Therefore, when at a later time he spoke of and recorded the coming of the Messiah (Dan. 9:24-27), everyone listened. Six hundred years later they were still watching and waiting for Daniel’s Messiah. The ancients believed that the gods controlled the events of life, which added emphasis to Daniel’s prophecies after his grand re-entry into the royal court.

But interest in a Jewish messiah predates Daniel. Even in the days of Moses there was a Balaam who blessed the Israelites when he was asked to curse them. But was this pagan prophet important? When considering that a shrine was built in the 8th or 7th century B.C., and that was centuries after he lived, then the only reasonable conclusion is that this man had god-like status in community. Along with that, his words were equally important. When he blessed the Israelites, everyone knew it and paid attention to the prophecy he gave about a future messiah. Now the obvious question is, did the magi know about it. Well, if Balaam was so important, how could the magi not have known of him…or of Daniel?

[1]. Some sources indicate 55 B.C.

[2]. Jayne, “Magi.” 4:31-34.

[3]. Hagner, “Matthew 1-13.” 29; Archer, Encyclopedia of Biblical Difficulties. 318.

[4]. Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament. 1:20.

[5]. Bullinger, Figures of Speech Used in the Bible. 639.

[6]. Bock, Jesus According to Scripture. 69.

[7]. Packer, Tenney, and White, eds. The Bible Almanac. 187-91.

[8]. Justin Martyr, Selections from Justin Martyr’s Dialogue with Trypho, a Jew.

[9]. Brown, Birth of the Messiah. 169-70.

[10]. Isa. 60:6; Jer. 6:20.

[11]. The religious group known as “Magians” is mentioned only once in the Qu’ran 22:17, the holy book of Islam that originated more than six centuries after Jesus. See http://corpus.quran.com/concept.jsp?id=magians. Retrieved December 2, 2012.

[12]. Johnson, “Matthew.” 7:257; Hagner, “Matthew 1-13.” 25.

[13]. In pagan cultures, astronomy and astrology were a single discipline of study. Balaam was probably from the Babylonian School of Astronomy and Astrology (cf. Num. 24:17).

[14]. Keller, W. The Bible as History. 364-65.

[15]. Geikie, The Life and Words. 1:559; Geating. “The Star of Bethlehem.” 121.

[16]. Humphreys, 51-52.

[17]. Dio Cassius, Roman History. 54.29.

[18]. After the destruction of the temple, Rabbi Akiva ( A.D. 50-135) was the founder of a great learning center in Jaffa and today is considered to be the father of rabbinic Judaism. He was killed by the Romans for supporting the messianic figure Simon bak Kokhba.

[19]. For further study, see Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History. 4:6; Dio Cassius, Roman History. 69:12-14.

[20]. Carson, “Matthew.” 8:90; Beasley-Murray, Preaching the Gospel. 38-40.

[21]. See 03.06.03 and 03.06.04 for more information on his demonic actions.

[22]. See Appendix 26; http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Magianism Retrieved June 26, 2015.

[23]. Schaff. “Magi.” Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. 3rd ed. 1385-86.

[24]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:144.

[25]. Jayne, “Magi.” 4:31-34.

[26]. The Babylonians, followed by the Persians, who in turn were followed by the Parthians, all had a reputation for predicting the future. Two ancient writers who made specific mention of this art among the Persians are Cicero, De divinatione 1.47 and Plutarch, Alexander and Caesar 3.2. See also Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible. 472.

[27]. Masterman, 1:472.

[28]. Matthew 3:9; 8:10-12; 15:28; 21:43; 22:5-10; 24:14; 28:19.

[29]. The grandson of Cyrus I.

[30]. See “Cataphracts” in Appendix 26.

[31]. See 03.05.18.

[32]. Stearman. “Those Mysterious Magi.” 9, 10.

[33]. See 04.04.07.Q2?

[34]. Vincent, Word Studies in the New Testament. 1:20; Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:153-54.

[35]. Two examples are: 1) Ron Charles, who has gathered scores of fanciful legends and myths, mostly written between the sixth and sixteenth centuries, that pertain to the life of Christ in his book titled, The Search: A Historian’s Search for Historical Jesus. (Self-Published, 2007); and 2) Nicholas Notovich, whose book, The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ. Trans. (Virchand R. Gandhi, Dover Pub.) is a so-called historical account of when Jesus went to Asia to study between the ages 13 and 29.

[36]. See Appendix 26; http://www.thefreedictionary.com/Magianism Retrieved June 26, 2015.

[37]. Eddy, The King is Dead. 67.

[38]. The fragment known as TM 393, mentions in 11.24-29. It was translated and published by W. B. Henning under the title of “The Murder of the Magi.” Journal of the Royal Academy Society. London: 1944, 133-44.; See also Eddy, The King is Dead. 68-69.

[39]. See 03.02.04 and 03.02.05.

[40]. The words of Josephus were specifically directed toward the Zealots fighting the Romans in the First Revolt (A.D. 66-70). However, this was a deeply held opinion for well over a century among the Jews.

[41]. See 12.03.01.Q1 “What ‘Messianic problems’ did the Jewish leaders have with Jesus?” and 12.03.01.A “Chart of Key Points of the Messianic Problems.” See also 02.03.09 “Messianic Expectations”; 05.04.02.Q1 “What were the Jewish expectations of the Messiah?” and Appendix 25: “False Prophets, Rebels, Significant Events, and Rebellions that Impacted the First Century Jewish World.”

[42]. See 03.05.24 “42 – 38 B.C. Messiah Predicted by Roman Poet Virgil.”

[43]. Barclay, “Matthew.” 1:26-27.

[44]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:145-47.