03.06.04 4 B.C. The Death of Herod the Great

Herod constructed and reconstructed a number of fortresses, huge temples, and other buildings. The following is a summary of his projects only within the Jerusalem vicinity.

- He remodeled and enlarged the Jewish temple built by Zerubbabel five centuries earlier. The construction began in 20/19 B.C. and ended in A.D. 62, decades after Herod’s death – only a few years before the Romans destroyed it.[1]

- In Jerusalem, he rebuilt a beautiful palace for himself in the Upper City by the gate that is known today as the Jaffa Gate.[2]

- He built three massive towers near his palace and named them after his friend Hippicus, his brother Phasael, and his favorite wife, Mariamne.[3]

- At the northwest corner of the temple was the Bira or Baris Fortress (Neh. 2:8; 7:21) that was rebuilt in the second century B.C by the Hasmoneans. In 35 B.C. Herod enlarged and renamed it the Antonia Fortress.[4] It is called a “barracks” in Acts 21:37 and is where Paul gave an address to the Jews in Acts 22:1-21. Pilate may have judged Jesus there or at his palace at the western end of the city.

- He built the Herodian palace-fortress with a splendid tomb for himself just south of Bethlehem. In doing so, the top of one small mountain was placed on the top of another.[5]

- He built a theater within the city limits of Jerusalem.[6] Its location remains a mystery although seat tokens have been found.

- He built a hippodrome but its location is also unknown.[7] The model 50:1 first-century model of the city of Jerusalem at one time placed it within the city, but recently it was removed as scholars continue to debate the location.[8]

- A water channel, or aqueduct, that brought water from a spring near Bethlehem to serve the temple. This pipe was ten miles long from beginning to end and had a drop of only 200 feet – and incredible engineering feat. However, Herod died before its completion, and when Pilate raided temple funds to complete the project, the Jews rioted.[9] One ancient writer said it was lined with lead and lime mortar, which is probably an accurate report.[10]

- Herod at one time stole more than 3000 talents of silver from King David’s tomb. However, after an angel of the Lord killed two of his guards, he immediately constructed a beautiful memorial over the tomb.[11]

- Finally, within Jerusalem he built five impressive porticoes, each about 27 feet high, around and across the twin pools of Bethesda (Jn. 5:2).[12]

For his architectural achievement, Herod certainly deserves the title of “the Great.” However, his personal and political life was a disaster. In his final years, he became miserably ill and in a great deal of pain. He frequently went to the hot springs of Hammat-Tiberias (in Tiberias), or to his preferred hot springs in Callirrhoe, east of the Dead Sea to find the relief he so desperately desired. At the age of seventy, the brutal life of Herod ended. His reign can be delineated into three distinctive periods.

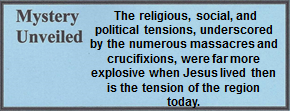

- Even though he was titled “King of the Jews” by the Roman senate in 40 B.C., he had to fight various nationalistic factions as well as the Parthians from 40 to 37 B.C. Thereafter, from 37 to 25 B.C., he consolidated his power and he eliminated rebels and challengers to his throne.

He was always suspicious of anyone he perceived to be a challenger to his throne.[13] For that reason, his body guards were from Galatia, Thracia, and Germany.[14] When Queen Cleopatra of Egypt committed suicide in 30 B.C., Emperor Augustus sent the 400 body guards she had to serve Herod.

- From 25 to 13 B.C. was a period of massive building projects, stability, growth, and expansion. During this period the Jewish people prospered even though there was a two-year drought that caused widespread famine (22-21 B.C.). It is for his success in construction and economic growth that he was titled “the Great” by historians.

- Finally, from 13 to 4 B.C. he was plagued with a diversity of problems within his family and his own mental instability. Fearful of losing his throne, he became extremely paranoid, thinking that his closest family, as well as others, would overthrow him.

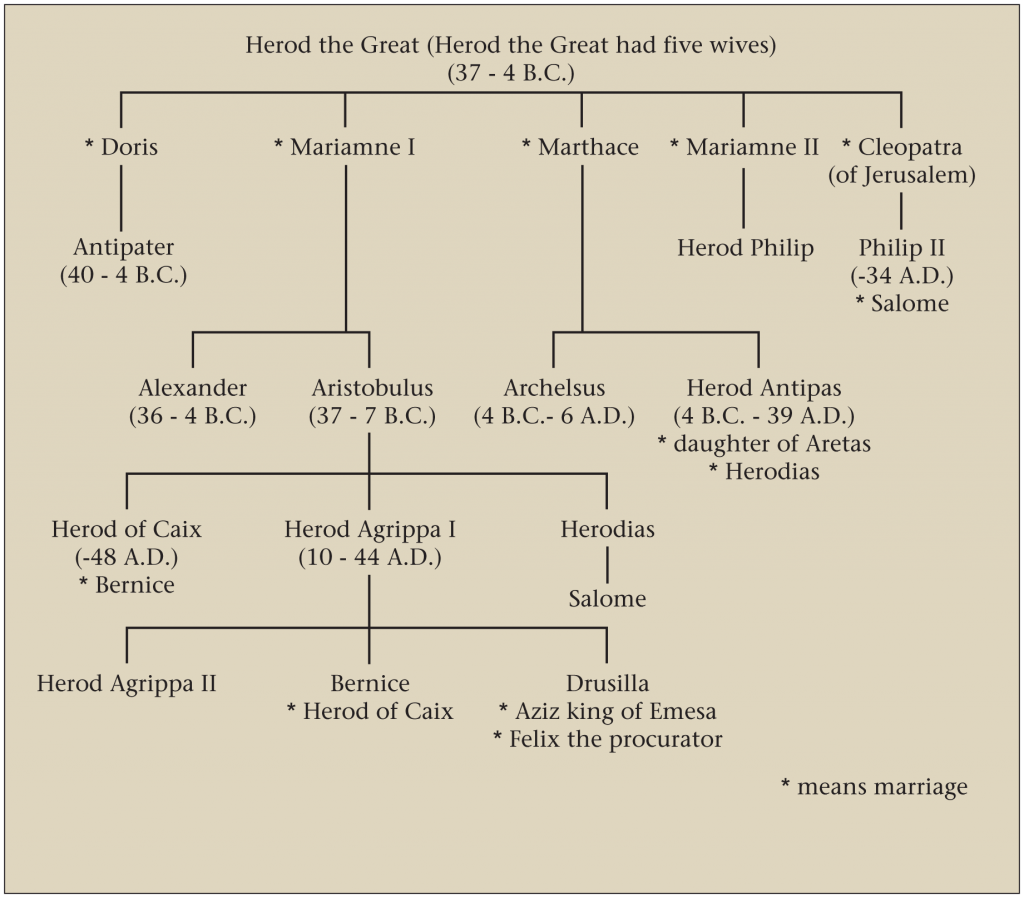

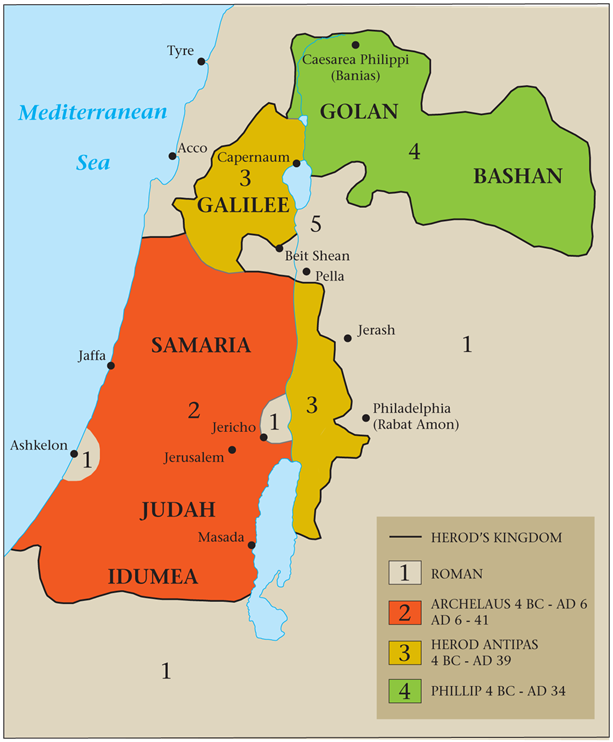

The longer he ruled, the more his life disintegrated. While he was a great architect and administrator, his personal life was in shambles. He exploited his subjects and family. He murdered innocent people of whom he became suspicious. He usurped the kingdom of his sovereign from the last unfortunate Hasmonean. To legalize his treachery, he married a Hasmonean princess, Mariamne. From this point on, his ruthless tactics went unchecked within his own family. A summary list of survivors is as follows:

- Herod’s first wife was Doris. Together they had a son, Antipater, who was beheaded shortly before Herod’s death. He divorced Doris.

- Herod’s second wife was Mariamne and they had two sons, Alexander and Aristobulus, both of whom were strangled to death by Herod in 7 B.C.[15] She also had two daughters Salampsis and Kypros. Salampsis married her first cousin Phasaelus, and they had three sons and two daughters. Mariamne was a Hasmonean princess.

- Malthace was a third wife with whom he had two sons, Archelaus and Antipas and a daughter, Olympias. Antipas married Herodias whose first husband was Herod (son of Mariamne). Malthace was a Samaritan woman, whom Herod probably married in an attempt to make peaceful a relationship with the Samaritans.

- In 24 B.C., he married his fourth wife, Mariamne who was the daughter of Simon Boethos, the high priest of Alexandrian origin.[16] Together they had a son Herod who was the first husband of Herodias (daughter of Aristobulus and Bernice). This Mariamne is not to be confused with his second wife by the same name whom he killed earlier in 29 B.C.

- Then came Cleopatra of Jerusalem which whom he had two sons, Philip and Herod. Philip married Salome, the daughter of Herodias who was the wife of Herod and Antipas.

- Pallas with whom he had a son named Phasael.

- Phadra, who had a daughter named Roxana

- Elpis, who had a daughter named Salome

- Name unknown – a brother’s daughter, no children.

- Name unknown – a sister’s daughter, no children.

Thus, some scholars believe Herod the Great had five wives, but others say the number could have been as many as ten. He also had nine sons and five daughters. The king most certainly had several other partners as well,[17] because Josephus said that at one time he gave a concubine as a gift to King Archelaus of Cappadocia.[18] His personal life was an on-going disaster filled with bribery, broken loyalties, lustful sex, scandalous banquets, revenge, and murder. Those who survived were said to be more miserable than his victims.[19]

His enemies, knowing his sense of suspicion, had taken advantage of every opportunity to portray Mariamne (wife # 2) as an unfaithful queen. So he had her executed, but when he realized his horrific error, his mental illness became obvious to everyone. He would lament over her, he would call her as if she was still alive, for a while he even gave up all affairs of state and even fled to Samaria where he had married her to seek relief from his haunting guilt. He finally fell into an unpredictable state – sometimes sane, sometimes insane. There were many in his immediate family who were murdered, not to mention others who also met their end at his hand. A summary list of those who died is as follows:

- In the year 37 B.C., Herod, with the help of his friend Mark Anthony, had Mattathias Antigonus executed. Herod then proceeded to have 45 associates of Antigonus executed.[20]

- The grandfather of his second wife, Mariamne, and her brother, both died at his command.

- In 35 B.C., Herod had his 17-year old brother-in-law, Aristobulus of the Hasmonean dynasty murdered. The young man was to be the high priest in the temple. For some reason, Herod became distrusting of the youthful priest and had him drowned by “accident” in the royal pool of his Jericho palace. Thereafter, Ananelus resumed the priesthood while Herod and all of Jerusalem deeply mourned for the young man’s death.[21]

- He condemned his brother-in-law, Joseph, to death.

- In 30 B.C., he had his brother-in-law, John Hyrcanus II strangled over an alleged overthrow plot.[22]

- In 29 B.C., he had Mariamne, his favorite wife murdered on a baseless suspicion. Afterwards he wept bitterly and had illusions that she visited him.[23]

- About the year 28 B.C., he had Alexandra, the mother of his wife Mariamne, murdered.[24]

- His death squads also killed two friends, Dositheus and Gadias.

- Around 20 – 19 B.C., about the time he began to rebuild the temple, he established an internal spy network and arrested those whom he suspected of a revolt. Most of them were taken to the Hycania Fortress[25] where they met their end.[26]

- Rabbi Ben Buta was a mild mannered rabbi who spoke against Herod, and for this his eyes were gouged out.[27]

- A distant kinsman Cortobanus died an unnatural death. Herod was highly suspected.

- Dosithai was a zealous opponent of Herod, and unfortunately, the long arm of Herod put an end to his life.[28]

- In the year 7 B.C. he had 300 military leaders executed.[29]

- Mariamne and Herod had two sons, Alexander and Aristobulus, both of whom were strangled to death by Herod in 7 B.C.[30] She also had two daughters Salampsis and Kypros. Salampsis married her first cousin Phasaelus, and they had three sons and two daughters. Mariamne was a Hasmonean princes.

- In 4 B.C. Herod was near the end of his life and still constantly threatened that power, wealth, and authority would be taken from him. In spite of being well-grounded in Jewish sensitivities, he had his soldiers hang a golden eagle over the temple gate. It was the Roman custom to hang golden shields in all the temples and dedicate them to the gods as an acknowledgement of some deliverance, or thankfulness in health and fortune.[31] However, two rabbis, Judah of Sarafaus and Matthew of Margoloth with their followers, tore down the Roman icon. They were soon captured and sent to Jericho where they were burned alive. Josephus reported that on that night of their execution there was a lunar eclipse.[32]

- Herod believed that the high priest was involved in some way with Rabbi Judah of Sarafaus and Rabbi Matthew of Margoloth. So the priest was tied to the corpse of one of his rebels. Consequently, the high priest died a slow and agonizing death as the corpse decayed.

- When he was about to die, he ordered the death of another son, Archelaus, but the order was never carried out.

- In 4 B.C., his son, Antipater, was beheaded at his command.[33] This was only five days before Herod’s own death. Antipater, the son of Herod’s wife Doris, was buried at the Hyrcania Fortress without honors or ceremony.[34]

Unfortunately, the list above is not complete, as any pretender to his throne made him tremble. His reputation of cruelty was well known throughout the empire. The Roman historian Macrobius recorded these choice words of Caesar Augustus concerning him:

On hearing that the son of Herod (Antipater),[35] had been slain when Herod ordered that all boys in Syria under the age of two be killed, Augustus said, “I’d rather be Herod’s pig than his son.”

Macrobius, Saturnalia 2.4[36]

Augustus no doubt used a deliberate play on words, as in Greek the words pig and son sound similar.[37] Furthermore, pigs were a forbidden food to the Jews, and hence, Herod would permit pigs to live in peace. His family died out within a century with one or two obscure exceptions.[38] There is little question, when considering how many of his own family Herod ordered to be killed, that he was completely capable of murdering innocent little boys in Bethlehem in order to wipe out any possible challenger to his throne.

Amazingly, some critics of the gospels in the past century have stated that the slaughter of the innocent boys in Bethlehem is mythical. They say there is no proof that his personality would command such an act. On the other hand, psychiatrists have debated whether he was paranoid schizophrenic or had a similar mental disorder.

Yet, among his numerous acts of terrible wickedness, there were acts of kindness. His international reputation was favorable not only among the Romans, but also among Jews scattered in the Diaspora. He contacted other monarchs, intervening on behalf of Jews in their countries and, thereby, making life easier for them. Consequently, foreign Jews loved him while those at home hated him.

03.06.04.A. THE FAMILY TREE OF HEROD THE GREAT. This genealogical chart shows the only relationships of significant descendants to each other. Herod could have killed more of his family than are shown. Courtesy of International Mapping and Dan Przywara.

The following image can be found in the full single-volume eBook of Mysteries of the Messiah as well as in the corresponding mini-volume. Search for the following reference number: 03.06.04.B. NASA GRAPHIC OF THE LUNAR ECLIPSE ON MARCH 12, 4 B.C. The Voyager astronomy computer program indicates that there was a lunar eclipse over Jerusalem on March 13, 4 B.C. If this is the eclipse Josephus meant, then the birth of Jesus would have been as early as 5 or 6 B.C. Graphic courtesy of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

The last months of Herod’s life were misery beyond description. Being in constant fear, he immediately killed those he imagined would challenge his throne, and he removed a son from his last will and testament. In a single day he deprived Matthias the position of high priesthood, and had another Matthias and his companions who raised a conspiracy, burned alive. That night, as if an ominous sign came from heaven itself, Josephus said that there was an eclipse of the moon.[39]

The day of Herod’s death was a festival for the Jews. His death was recognized by Josephus to be a divine judgment and he said it was as if eternal hell came upon him as various horrible diseases slowly engulfed him. The historian said,

But now Herod’s distemper greatly increased upon him after a severe manner, and this by God’s judgment upon him for his sins: for a fire in him glowed slowly, which did not so much appear to the touch outwardly as it augmented his pains inwardly; for it brought upon him a vehement appetite to eating, which he could not avoid to supply with one sort of food or other. His entrails were also exculcerated, and the chief violence of his pain lay in his colon; an aqueous and transparent liquid also settled about his feet, and a like matter afflicted him at the bottom of his belly. His private member was putrefied and produced worms, and when he sat up, he had a difficulty of breathing, which was very loathsome, because of the stench of his breath and the quickness of its returns. He had convulsions in all parts of his body, which increased in strength to an insufferable degree.

He also sent for his physicians and did not refuse to follow what they prescribed for his assistance; and went beyond the river Jordan, and bathed himself in the warm baths (natural hot springs) that were at Callirrhoe … which water runs into the lake called Asphaltitis (Dead Sea).

Josephus, Antiquities 17.6.5 (168-171)[40]

Amazingly, his body began to putrefy while he was still alive. Worms consumed his organs as he groaned in agony. He burnt up with fevers, gasping air; he could hardly draw his tainted breath. He attempted suicide, but that failed.

There simply was no relief for the dying king. He had a personal physician, but all the physicians in the land could not bring him comfort.[41] Herod’s final act was to gather all of the prominent men of Judea and Israel together in his hippodrome in Jericho. He instructed his assistants to kill them at the moment of his death, as he feared that there would be no mourners. Josephus tells that he died a painful, prolonged, and agonizing death at age 70.[42] When his life departed, fortunately, his assistants failed to carry out his orders.[43] Ironically, he died on the Feast of Purim and there was much rejoicing at the death of Herod the wicked.[44] His body was buried in a hidden area of the southern fortress-palace, the Herodian which has now been found. Josephus described the lavish funeral appointments:

The bier was of solid gold, studded with precious stones and draped with the richest purple embroidered with various colors. On it laid the body wrapped in a crimson robe, with a diadem resting on the head, and above that a golden crown and the scepter by his right hand.

Josephus, Wars 1.33.9 (671)

Many breathed a sigh of relief upon his demise. By his ten wives and many concubines, he had nine surviving daughters and five sons who miraculously outlived him. However, God’s judgment was to come, as within a century the entire Herodian family dynasty was utterly destroyed by disease and violence.

Prior to Herod’s reign, the country enjoyed prosperity with low unemployment as he was determined to bring the glory of Rome to Jerusalem. Even in the early years of this reign, the nation faired well. However, his greed drove the nation into bankruptcy, financially and morally. Upon his death, the nation was demoralized by the Hellenistic inroads and impoverished by the high taxation – Judea alone had to pay 600 talents annually.[45]

Note the words of the historian:

When he took the kingdom, it was filled in an extraordinary flourishing condition, he had filled the nation with the utmost degree of poverty; and when under unjust pretenses, he had slain any of the nobility, he took away their estates and when he permitted any of them to live, he condemned them to the forfeiture of what they possessed. And, besides the annual impositions which he laid upon every one of them, there were to make liberal presents to himself, to his domestics and friends, and to such of his slaves as were vouchsafed the favor of being his tax gatherers, because there was no way of obtaining a freedom from unjust violence without giving gold or silver for it.

Josephus, Antiquities 17.11.2 (307-08)

With his passing, those with nationalistic dreams were motivated to revolt against the Herodian Dynasty and the Romans. In fact, there were so many revolutionary movements, that historians have difficulty counting them. Would they have been an organized cohesive force, the Romans would have had a serious challenge. Josephus said there were “ten thousand other disorders in Judea,” [46] which might have been an exaggeration, but clearly stated the war-like tension of the time. Among them were two thousand of Herod’s old soldiers who fought against the Herodian dynasty. The final outcome was not written, but it is assumed they were either killed in battle, crucified, or fled the country.[47]

[1]. When Jesus spoke with the Jews in A.D. 27 and said that if the temple would be destroyed He would raise it in three days (Jn. 2:20), Herod’s temple was still under construction, but Jesus was referring to Himself as the “Temple.” See 03.05.31.B.

[2]. Josephus, Wars 5.4.4 (176-83).

[3]. Josephus, Wars 5.4.3-4 (171-76).

[4]. Josephus, Wars 5.5.8 (238-47). A model of the Antonio Fortress can be seen at the upper right corner of the Temple enclosure on 03.05.31.B.

[5]. See 03.05.26.C and 03.05.26.D.

[6]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.8.1 (268). See 03.05.26.H.

[7]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.8.1 (268); 17.10.2 (255); Wars 2.3.1 (44). See 03.05.26.F.

[8]. Visitors today can see the model of first-century Jerusalem at the Israel Museum, behind the Shrine of the Scroll (Dead Sea Scrolls).

[9]. Josephus, Antiquities 18.3.2 (60); Wars 2.9.4 (175). See 09.03.08.A and 10.01.20.A.

[10]. Pseudo-Aristeas 90. At this time lead was a relatively new metal to the ancient world and its bio-hazard qualities were unknown. Lime mortar was used for centuries as a sealant in water cisterns and aqueducts.

[11]. Josephus, Antiquities 16.7.1 (179-82); Wars 7.9.1 (392).

[12]. Scholars debate the date of the construction as well as whether Herod built it. The consensus is that he did, but future archaeological discoveries may prove otherwise.

[13]. For example Josephus said that once the Pharisees plotted, with some women in Herod’s court, to have him put to death. See Antiquities 17.2.4.

[14]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.8.3.

[15]. Josephus, Antiquities 16.11.7-8 (392-394).

[16]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:50.

[17]. Scholars who believe that polygamy disappeared may have to reconsider their position. Johannes Leipoldt in Jesus und die Frauen, Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer, 1921 (reprint 2013), 44-49, gives a number of examples in his notes. See also Jeremias, Jerusalem in the Time of Jesus. 93.

[18]. Josephus, Wars 1.25.6 (511).

[19]. Metzger, The New Testament. 44-45; Pasachoff and Littman, Jewish History in 100 Nutshells. 59-61; Farrar, Life of Christ. 19.

[20]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.1.2 (5-10).

[21]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.3.3 (50-56).

[22]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.6.2-3 (173-178).

[23]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.7.4 (222-236).

[24]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.7.8 (247-251).

[25]. The Hycania Fortress was one of several fortresses along Herod’s southern border. See map at 03.05.26.Z.

[26]. Josephus, Antiquities 15.10.4 (365-372).

[27]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:227.

[28]. Geikie, The Life and Works of Christ. 1:227.

[29]. Josephus, Antiquities 16.11.7-8 (393-394).

[30]. Josephus, Antiquities 16.11.7-8 (392-394).

[31]. Josephus did not record this event, probably because his source of information was Herod’s personal friend and historian, Nicholas of Damascus. But neither did Nicholas record the slaughter of infant boys in Bethlehem. The burning of the rabbis and their students was recorded by the Jewish philosopher, Philo of Alesandria in Embassy to Gaius. 38:299-305.

[32]. Josephus, Wars 2.1.2 (5) and Antiquities 17.6.2-4 (149-167, esp. 151).

[33]. Some scholars believe that Doris was Herod’s concubine or “consort,” rather than his wife.

[34]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.7.1 (182-187).

[35]. Insert mine for clarification. The son was Antipater whom Herod the Great ordered killed five days prior to his own death.

[36]. Farrar citing Microbius, Saturnalia, II.4 in Life of Christ. 19; Johnson, “Matthew.” 7:260.

[37]. Another example of a wordplay is a statement by Jesus when He quoted Psalm 118:22 in the Parable of the Wicked Tenants (Mt. 21:42-44). There, the words “stone” and “son” sound similar in the Hebrew and Aramaic languages. (See 13.03.05).

[38]. Geikie, The Life and Words. 1:570.

[39]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.6.4.

[40]. Insert mine.

[41]. Josephus, Wars 1.1.5 (657).

[42]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.6.1 and Wars 1.23.1.

[43]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.6.5; 17.8.1-4; Kokkinos, “Herod’s Horrible Death.” 28-35, 62.

[44]. For the origin of Purim, see Esther 8:15-17. Chronology established by Eugene Faulstich, “Studies in Old Testament and New Testament Chronology.” 110.

[45]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.11.4 (320). That was a huge sum and, according to Tacitus (Annals 2.42), in the year A.D. 17, the provinces of Syria and Judea begged to have their taxes reduced, but their petition was denied. See also 02.03.03 “Economy.”

[46]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.10.4.

[47]. Josephus, Antiquities 17.10.4.

03.06.00.A. BIRTH OF THE SAVIOR. Artist Unknown. The miraculous births of various prophets in the Old Testament Era ended with John the Baptist who was born to elderly parents, but these incredible events were superseded by the virgin birth of Jesus.

03.06.00.A. BIRTH OF THE SAVIOR. Artist Unknown. The miraculous births of various prophets in the Old Testament Era ended with John the Baptist who was born to elderly parents, but these incredible events were superseded by the virgin birth of Jesus. 04.05.00A. JOSEPH, MARY, AND JESUS RETURN FROM EGYPT. Artwork by William Hole of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art, 1876.

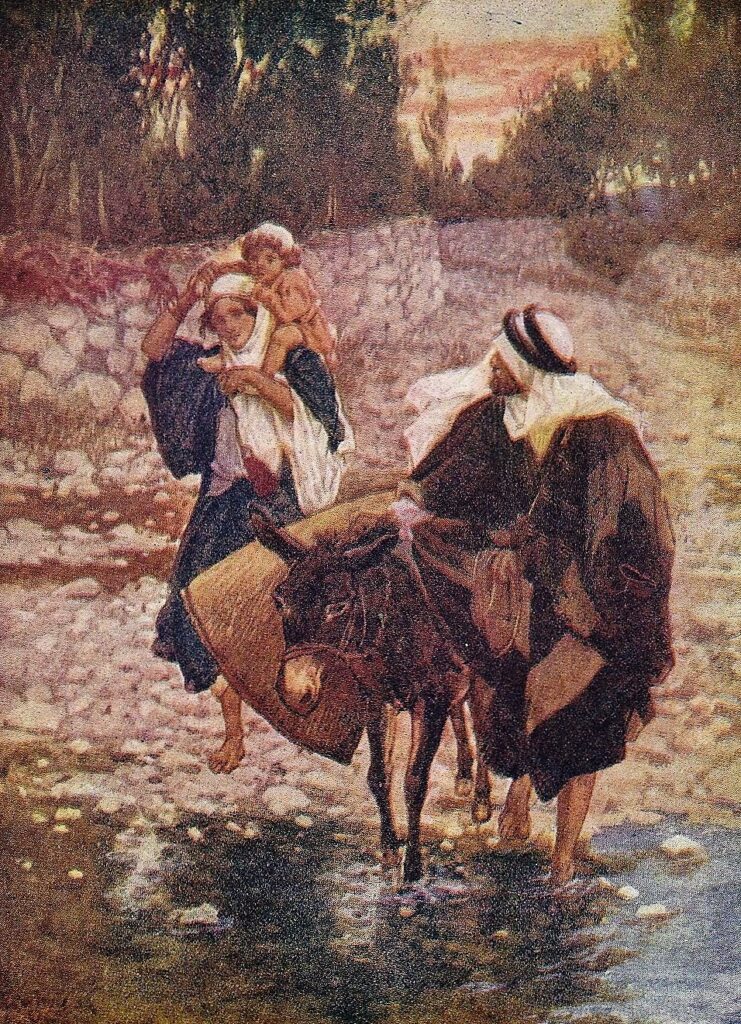

04.05.00A. JOSEPH, MARY, AND JESUS RETURN FROM EGYPT. Artwork by William Hole of the Royal Scottish Academy of Art, 1876.